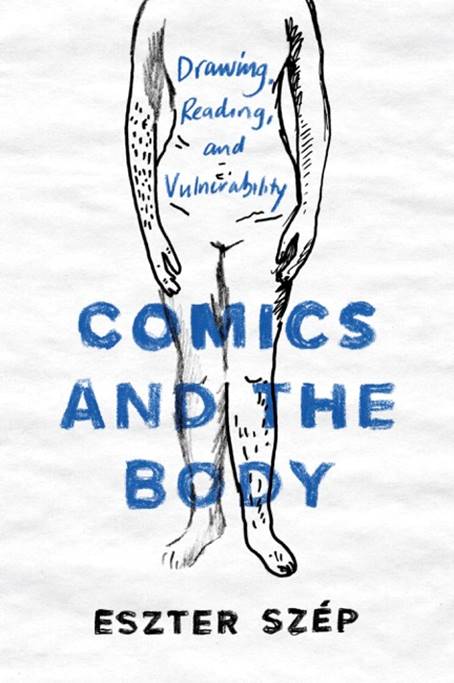

Comics and the Body: Drawing, Reading and Vulnerability

Comics and the Body: Drawing, Reading and Vulnerability

Eszter Szép

Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2020

220 pages

ISBN 9780814214541 (cloth) | ISBN 0814214541 (cloth) | ISBN 9780814280805 (ebook) | ISBN 0814280803 (ebook)

Eszter Szép’s monograph, Comics and the Body: Drawing, Reading and Vulnerability, was published by The Ohio State University Press in 2020. The interdisciplinary project connects two current trends in comics scholarship: the consideration of the roles of the body of the artist and that of the reader in creating and reading the comics. Szép also employs an innovative method in which the bodies of the artist, the reader, and the comic itself are examined through the lens of vulnerability, thus shifting the focus away from trauma. What truly sets her monograph apart from other publications about comics, however, is that Szép explores both creating and reading comics as performative, embodied forms of engagement, as well as the ways in which these activities are in interaction with each other.

The book begins with an introductory chapter that gives a thorough and extensive review of the theoretical background on which Szép bases her own theories and analyses. She explores the implications of the drawn line—both in the fields of comics and in art history—including what it means for a line to be authentic—rooted in a rather skeptical attitude towards trained artists— and how drawing can be interpreted as organized thinking that embodies the artists’ subjectivity. Szép ultimately argues that “vulnerability can be more than a central topic of nonfiction comics—it can also be seen as a central experience expressed by drawing” (50). The book has five chapters of case studies besides the introduction putting theories into practice, that is throughout which the drawn line is traced all the way to the body of the reader. Szép’s corpus for the case studies consists primarily of non-fiction comics. She argues that the significance of the genre lies in the fact that due to their “special and multiple connections to reality, real events, and real people, the link between their embodied and performative nature and vulnerability is easier to see” (50). The conclusion of Comics and the Body is a revolutionary metatextual exploration of Szép’s theories and ideas in the form of a short comic, seamlessly falling in line with the topic and theme of the book.

The first section of case studies focuses on the interpretation of comics (and the artist), while the second part concentrates on the reader. Chapter one is centered around Linda Barry’s What It Is and Syllabus. Barry’s comics have a metatextual element to them, theorizing about lines, drawing, and the nature of the creative process. Szép argues that for Barry the line is not simply an extension of the mind or the body, but also that if the need for control is given up, it becomes authentic, and steps up as a “partner” in creation. The release of control is exactly what allows vulnerability to appear on the page, through the drawn lines themselves.

Ken Dahl’s Monsters is the focus of the second chapter. The comic is a semi-autobiographical exploration of the body with herpes. Szép calls the body of the main character in the comic, representing the author, the “autobiographical avatar” (79). This avatar constantly changes throughout the three parts of the comic, as the body undergoes visceral, sometimes abject symptoms and changes, both medically and psychologically. Its transformations provide an interesting representation of the socially positioned, ever-changing, fluid body, and as Szép points out, this in turn embodies the performative power of the line in comics through the “cartoon body’s” (93) ever-changing, in-transition shapes, forms, and lines.

The third chapter of the book brings a slight change in the focus of the argument. Szép turns from the metanarrative, autobiographical comics to ones that—although still nonfictional—tell other people’s stories, and with this change in interest, the reader is moved to the center of attention. Joe Sacco’s Safe Area Goražde and The Fixer can be categorized under comics journalism and deal with the traumas of war and poverty. Szép explores the embodied engagement of the reader through these two examples, via the tactility of surfaces, while Sacco’s technique is seen as “ethical engagement” (110) with the vulnerable nature of the topic and the subjects that are present in his stories.

Miriam Katin’s We Are On Our Own and Letting It Go are graphic memoirs, the first describing survival in World War II, the other is about one’s personal fears. Szép refers to these two comics when discussing reading as an embodied performance, an ethical encounter between the reader and the comic. She argues that through reading the (reader’s) body can experience vulnerability through meaning-making while reflecting on their own bodies. In arguing thusly, she relies on Robert Bernstein’s theory on “scriptive things” (164), which is defined as elements that can prompt and inspire actions in people. Comics are understood then as “scriptive things” that can inspire empathy and vulnerability in the reader. Szép explores three ways in which this can happen through the act of reading: through immersion, through a body-schematic performance, and through abjection and visceral seeing.

Katie Green’s Lighter Than My Shadow and Joe Sacco’s The Great War are the topic of analysis in the last chapter, where Szép explores the exciting relationship between the materiality of the comic, the haptic experience of reading, and how reading can connect and relate to the body of the reader to create a special tactile embodied experience, which Szép calls the holistic experience of reading. Green’s comic is centered on anorexia, and the heavy and thick material representation of the comic stands in very interesting opposition with the topic of the memoir, where the character is getting smaller and smaller, slowly disappearing off the pages. Sacco’s The Great War is made up as a panorama: as one long, single strip of paper with no central character but many identical ones, recreating the Battle of the Somme on paper. The physical makeup of the comic creates an uncomfortable reading experience, and because the material is unstable, the bodily experience will lead to a different reading as well. Szép argues through these examples that the “materiality of the comic adds an extra channel in which the discourse of vulnerability can manifest” (181).

Szép’s concluding chapter utilizes the theory she had presented throughout the book by summarizing the content through a comic to “line things up.” By using an “autobiographical avatar” of herself, different textures and types of lines, and creating vulnerable ways of representation, she evokes the different chapter topics in a visual format, thus creating not merely an index of the topics but also a succinct synthesis of the book.

Szép’s monograph is a delicate and considerate exploration of vulnerability expressed and experienced through comics, successfully merging comics theories with embodiment theory. Through her case studies and her metatextual conclusion, she explores how the artist, the materiality of the comic (either the lines or the actual paper and book) and the reader is connected through an embodied experience of expressing and encountering vulnerability.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.