Introduction

The Great War was the grand culmination of long-brewing schemes and a series of turbulent events ushering in an equally troublesome century. In times like these, statesmen are often doomed to fail in their attempts to prevent catastrophe, as was the case with a series of Hungarian diplomats of vastly different social and ideological standings, who tried to undermine the Entente efforts to dismantle Austria-Hungary, and consequently, the historical territory of the Kingdom of Hungary. After these cataclysmic events, however, facing such a national tragedy, a Hungarian statesman emerged with plans to restore national unity not through arms, but through letters, through a set of cultural policy initiatives that were deeply rooted in Western thinking, but applied to the specific circumstances of post-war Hungary: Kuno Klebelsberg. A nobleman of international breed and education, he was an iconic Minister of Culture and an intriguing, complex figure of Hungarian history. In this paper, the authors examine how Klebelsberg intended to reinforce Hungarian cultural and national identity after the seminal events of 1920 not through the lenses of national victimhood and a turn towards the East, as was the tendency of many among the Hungarian elite (cf. Ablonczy 2016), but by a renewed commitment to Hungary’s Western heritage and to the country’s place in the European intellectual and academic traditions. The paper is designed to focus on the English/American aspects of the process, as Klebelsberg sought to achieve his goals in part by turning towards the USA that had a transformative, global commitment to science and culture after the war.

A Minister of Culture with International Renown

The starting point of Kuno Klebelsberg’s career was the fin de siècle prosperity of a long and peaceful period that came to an abrupt end with World War I. The Treaty of Trianon torn apart the country politically, economically, and culturally with the disintegration of the historical Hungarian state. Hungary became a small East-Central European state, with an economy in disarray and a thoroughly fragmented system of cultural institutions. The primary aim was to quickly consolidate the state, its economy, and to adapt to the new conditions brought about by the territorial losses and the subsequent economic downturn. These included the reduction of its territory from 283,000 square kilometers to 93,000 square kilometers, a population drop from 18.2 million to 7.6 million inhabitants, shocking the population and wreaking havoc economically with the loss of important industrial capabilities and sources of raw material (Molnár 2001, 262). The largely irrational and draconian measures of the Treaty of Trianon (June 4, 1920) determined the revisionist course the country took in the following decades and is still a source of national grievance and division in the present day. It is important to recognize, however, that the efforts towards modernization at the turn of the century were only partially successful and had to be continued – and thus, these two aims could be realized simultaneously. At the same time, the paramount political aim of the Treaty’s revision of influenced all political and cultural efforts. Virtually no political parties or actors accepted these new conditions, and as such, the hope of revision was the definitive leitmotif of the epoch to come.

In the 1920s, István Bethlen and his government were to attempt consolidation, which meant a conservative turn and a series of reforms for the whole country. The basic tenet of this policy was that the nation’s future existence and the sustainment of the state depended on the middle classes. These social groups proved to be the most ardent supporters of the postwar regime, led by Miklós Horthy. Besides industrial workers, the regimes’ social policies favored this middle and upper classes, thus, most of them were ‘natural allies’ to the government. Therefore, the new political programs of the decade represented primarily the interests of the middle class, and especially so regarding cultural policies. Kuno Klebelsberg, who gained a great deal of administrative experience before 1918 endeavored to oversee this latter field as Minister of Culture, but also to provide opportunities for education and economic advancement for other social groups and segments as well through his policies. Similarly to József Eötvös, Klebelsberg was a great politician, whose work and policies were motivated by the desire to modernize, and to elevate the cultural standards of the whole nation. He oversaw and influenced all cultural fields, from primary education to higher education, policies regarding arts and sciences, cultural heritage, public collections, state-funded theaters, the building of public playgrounds, and international sport diplomacy. Evidently, his efforts were multifaceted, and many of its results are still essential in Hungarian culture.

Many concise works were written about his career, its specific fields, and its aftermath, but a significant, definitive aspect of his work as Minister of Culture is quite often overseen: the European and international dimension of his work and of his personality. Klebelsberg was not simply an effective politician with large-scale activities and policies, but a truly European politician with a global perspective – not only because his achievements are remarkable even in a European context, but because he was an Europäer, with international standards and an international outlook. Whatever he set out to do, his point of departure was always a Western example, continuously comparing the scale of development and modernization to Western countries. No matter how wide the gap seemed to be, he was relentlessly pursuing to follow more developed countries quickly, and for these nation states to appreciate this fact. Klebelsberg’s was a difficult mission in post-war Hungary, but he was stubbornly insistent on building the image and the reality of Hungary as a European nation, and a “nation of culture”, as conceptualized by him.

He was predestined to do so by the Western orientation of his personal role model, István Széchenyi, but also by his own life experience, youthful endeavors, and studies. Besides Budapest, he studied in Berlin. His stay in the German capital and the country’s policies on science and system of education had a lasting impact on him. His intellectual development, and thus his later work as Minister of Culture, was greatly influenced by his renowned teachers. Also, later, he formed a closer relationship with Becker, later a Prussian Minister of Culture, which had an impact on his science policies and the ones regarding higher education. Although he successfully pursued a law degree, as was the custom of his age, he also studied a considerable deal of history both in Hungary and Germany – it is by no coincidence that he was the president of the Hungarian Historical Society from 1917 until his death. He spoke German and read several languages as the result of his home schooling and time spent in secondary school. His European identity is beyond debate, and so is his knowledge of the world and its affairs, his remarkable education, and continuous self-development.

It is well-known that the young Klebelsberg was rising rapidly through the administrative ranks, becoming a secretary to the Minister in 1914. His duties included overseeing institutions of higher education: he was the one to carry out the formation of two new universities in Debrecen and Pozsony (present day Bratislava), during which he relied on his German experience. This period can easily be seen as the precursor for his “university idea”. He was the one to establish the first-ever Hungarian academic state institution in Istanbul, yet another precursor for his future efforts in cultural diplomacy. He was the vice secretary at the Prime Minister’s office in 1917 for a few weeks, and Minister of Internal Affairs in the second Bethlen-government. He was asked to be Minister of Culture by Bethlen in 1922, from which point he was the chief architect of Hungarian cultural policy, although not all of his efforts were successful. He was not without faults, there were shortcomings and faulty elements in his designs, and his decisions were often affected by the dynamics of day-to-day politics. It has to be noted that he was the one to maintain the infamous Numerus Clausus Act,1 although he did not vote in the matter. When enacted, there was a major international uproar, followed by a League of Nations investigation. From 1925, international pressure was increasing to change this law, and Bethlen and Klebelsberg had to revise it eventually. Klebelsberg wrote the following to Bethlen: “This law will have to be revised, then. Not so that the swarms of Jewish students can pour over the nation, but so that through certain rational measures, the essence of the system could be preserved” (Szinai-Szűcs, 1972, 39.)2 Finally, a formal amendment was accepted in 1928, but it was still controversial. The often cited claim that his otherwise modernizing cultural policies had many elitist notions is also not without merit (Kovács M., 2011).

However, the aim of the present paper is to examine the European, and especially the English and American aspects of Klebelsberg’s cultural policies through his papers and public speeches, claiming that these Western dimensions, his enthusiasm for European and some North American cultural policies were definitive for his own decisions and initiatives. This is made easier by the multiplicity of sources, since Klebelsberg skillfully used media and other publications to promote his goals – yet another testament to his conservative, reformist thinking. He was ahead of his times in using the media too: he recognized the power of public opinion, and made every effort to win its support for his endeavors. He was the first Hungarian politician to address the general public, and not only a narrow circle of professionals and aristocrats. From time to time, he issued public addresses, and monitored the dynamics of public opinion. “This is why I roam the country, […] talking about the importance of my policy efforts. This is why I write so often, […] for the public to understand the importance of my efforts, and ask for their sacrifice […]. With my articles, I can address the Hungarian public and society directly” (Klebelsberg 1928, 7).When finishing or starting a project, he always put any emphasis on proper propaganda efforts, and his editorials appeared frequently in daily papers, including Pesti Napló, Nemzeti Újság, but his writings were also published in periodicals, such as Néptanítók Lapja, or Közművelődés, and local papers, such as Szeged’s Délmagyarország, or Szegedi Szemle. To increase his reach, he also had his articles collected and published from time to time.3 They used highly complicated sentence structures and many allusions, metaphors, and examples, adhering to the Neo-Baroque vogue of his day, and they had immense impact on his contemporaries. Moreover, these publications are invaluable and authentic sources for researchers. Another important detail worth mentioning is that some of Klebelsberg’s speeches were also published in foreign papers as part of his cultural diplomacy efforts. He published articles and speeches in Italian, German, and French papers, usually in connection to his diplomatic tours.

The ideological foundation of his work was moderate Christian conservatism, rooted in the Hungarian Reform Era, and characterized by two key features: neo-nationalism and cultural supremacy. The detailed presentation of these ideas was already carried out in other works, but it is worth clarifying generalities. When talking about nationalism, Klebelsberg revisits Széchenyi’s reformed view, and condemned the traditionally pessimistic, symbolism-fueled Hungarian take on the concept of the nation, exemplified by donning traditional clothes (although he also did it sometimes during formal events), and advocated instead a fruitful, active patriotic stance. However, the concept of cultural supremacy (the notions that Hungarians are more sophisticated and skilled than the surrounding nationalities), is a heritage from the late-19th century, but Klebelsberg did not accept it as a given fact, but saw it as a state to be relentlessly pursued. Through its results, Klebelsberg hoped to prove to the international public that Hungary does, indeed, have a place among European nations. According to him, the only course of action to take after Trianon is to expose Western powers and their public to the cultural value of Hungary, while also recognizing that such action takes immense effort and financial investment. We should interpret this conception of cultural supremacy as part of his desire for the country to belong to the “educated West”, which was understandable in a torn and humiliated post-war country, but was also a manifestation of Klebelsberg’s conviction that Hungary’s future is bound to Europe. He calls for a balance between tradition and modernity, that is, the preserving of national characteristics and the impact of European modernization that was needed in Hungarian industry, labor, and cultural contexts as well. This meant, in Klebelsberg’s interpretation as we will see, the adaptation of Western standards in cultural policy, including education from the most primary level to doctoral studies, the dotation of literary and intellectual efforts. He elaborates on this idea in many of his texts, but it is interesting to mention that this conservative thinker uses the poem “Góg és Magóg fia vagyok én…” by modernist Hungarian poet, Endre Ady, to justify his claims at one point. On the one hand, he defends Ady, whom he claims to represent the aforementioned balance by being Hungarian and European at the same time. On the other hand, he states that the poem symbolizes his efforts perfectly. “If we wish to prevail, we have to maintain our national character [Verecke], but also have to rise to a European level [Dévény], and learn from the nations surrounding us. How to create balance between these two perspectives – the future of our country is dependent upon this challenge” (Klebelsberg 1930, 48-50). This is how Klebelsberg summarizes Ady’s poem, highlighting that time will justify the poet’s claims (1930, 48-50).

Klebelsberg preferred Western patterns in almost every walk of politics and life, comparing his results, or shortcomings to Western standards, let those be the country’s level of illiteracy, or academic/science policy. Regarding the latter, he saw an example to follow not only in the German system of education so familiar to him, but in the “grand design of the system of community colleges in America.” He states that “the progress of cultural policy in America is remarkable, especially regarding the school system”, and postulates that this might be the reason for their increasing academic supremacy (1930, 214). There is no way to review all of his activities here, but in the following, the paper investigates the three most important areas for Klebelsberg: science policy, cultural diplomacy, as well as Hungarian institutes and scholarship programs in foreign countries.

An International Science Policy

The standard for Klebelsberg’s science and academic policy was the already implemented models and examples of Western universities, comparing the University of Pécs to Heidelberg and the University of Szeged to Göttingen (Klebelsberg 1930, 66-69). He wished to garner international support for and recognition of his efforts, for which the main example was German academic policy, but English and American examples were also important for him:

"It would be a grave mistake to weaken our ties to German academic life, which still plays a leading role in global academia today. However, the one-sidedness of our policy has to be corrected, and stronger connections are to be established to English and American academic life. The grand victor of the war was England, and the war, as well as the subsequent peace meant a period of great prosperity to America. They are the two leading powers today, and the situation is quite similar to the days when Széchenyi thought that our country should be oriented towards England." (Klebelsberg 1924, 640)

In other instances, Klebelsberg emphasizes the effectiveness of US researchers in the fields of natural sciences, praising and citing them as models, urging to follow their well-equipped institutes and the human and financial resources devoted to these fields (Klebelsberg 1930, 216). Based on these examples, he stressed the importance of natural sciences and organized a large-scale, international natural science conference in Budapest in 1926. This was done with the dual aim of promoting the value of these fields in the Hungarian public sphere, but even more importantly, to showcase Hungarian achievements to the Western public and academic life through prestigious European keynote speakers and guests, who observed this impressive representation of Hungarian scientific efforts. In his speech during the opening ceremony, he identifies the tasks of modernizing efforts on the basis of the German model:

"Contemporary progress is aimed at utilizing science in the process of production. Many of the institutes of the German academy were established to increase the competitive potential of German industry […], and upon their example, many nations, such as the English and the French, also recognized the fundamental importance of the work carried out in laboratories. Thus, the fostering of natural sciences became paramount in the cultural policy of developed nations. We need to understand this sign of the times, and must not lag behind these nations in our efforts." (1927, 150)

Klebesberg was also interested in developing Hungarian participation in the booming fields of natural and technical sciences. In other texts, he also urges Hungarian academics to “enter American academic life in the fields of natural sciences, economic studies, and technical fields. This is especially true for theoretical and applied natural sciences, specifically for their economic and technical use. In the future, I will be unwilling to give tenure to a professional gentleman in the field of economics who did not spend a longer period of time in the United States. That is the birthplace of the most modern forms and modes of production. The rhythm, the whole method of economic life is the freshest there, and without knowledge of this, our own economy cannot be correctly shaped” (1930, 217-218). Klebelsberg also regularly mentioned the United States in the context of medical research and the modernization of healthcare. He writes on one occasion: “The grand American patrons, the Carnegies, the Rockefellers devoted hitherto unimaginable sums of money to advance medical research, establishing large research institutes” (Klebelsberg 1927, 259). Thus, he made numerous efforts to build and maintain relationships between Hungary and the academic circles of the United States, with the aim of gaining support for Hungarian development initiatives. Besides direct financial support, he also created opportunities for Hungarian scholars to travel to the United States, and obtained grants for that reason, as shown below. The most successful relations were built with the Rockefeller Foundation, and Klebelsberg deeply appreciated its support not only in the form of their grants, but also in the contribution to the reconstruction of European heritage sites (Versailles) and the establishment of research institutes (German Mathematical Institute). “Here at home, too, there was a worthy Rockerfeller-fellow, Béla Johan, who has gotten a beautiful institute for his public health research”, writes Klebelsberg, referring to the fact that the National Public Health Institute, organized and led by Béla Johan4 in the next ten years, was built in Budapest in 1925 with funds from the Rockefeller Foundation. The activities of the medical researcher are one of the chief examples proving Klebelsberg’s vision right: Johan was studying the American public health system in 1922-23 as one of the first Rockefeller-fellows from Hungary, gaining further experience in European countries afterwards, and as a result, he was the one to successfully organize a similar institution in 1925, upon his return to Hungary, soon showing visible progress and success. It is no wonder that Klebelsberg was proud of his American relations, and regards Hungarian–American relations to be “beyond doubt, the main line of cultural policy for the 1930s” (1930, 219). However, the more professional, American-style cultural organization practices did not take root after Klebelsberg’s early death. Moreover, unfortunately, the realities of global and European politics did not prove him right, and US-Hungarian relations were severely damaged in the following decades.

The conference mentioned above was not the only major event taking place in Hungary, as there were many other congresses and conferences in Budapest, often opened and attended by Klebelsberg too. During his time in office as Minister of Culture, there were a number of important academic gatherings in Hungary, including international historical association meetings, medical conferences, a zoological congress, the international congress of architects, the 3rd Finno-Ugric Congress, and even an international congress of organ players, who had the chance to visit the freshly dedicated organ at the Votive Church of Szeged. Klebelsberg made every effort to publicize the cultural diplomatic importance of these events; for instance, he wrote the following about the zoological congress in an issue of the daily paper Pesti Napló in 1927: “The 10th Zoological Congress takes place on September 4th in Budapest, with its 500 participants, with scientists from all major nations from around the globe, including Australia and South-Africa. This provides us with the unique opportunity not only to welcome and host them with traditional Hungarian hospitality, but also to showcase to them the Hungarian achievements in their field, such as the Biological Research Institute in Tihany” (Klebelsberg 1928, 68). He also pointed out that the personal experience of the guests is worth more than any sort of propaganda, since they can observe first-hand the results of Hungarian efforts, which was, of course, of major importance with a view to international publicity. He wrote with satisfaction: “The new research institute by Lake Balaton, then, was established not only to serve Hungarian scientific efforts, but also to strengthen our nation’s reputation. The institute has an even more modern apparatus of equipment than that in Naples, and we can show this now to the whole world” (1928, 69).

Cultural diplomacy

Although Klebelsberg was often accused of having a one-sided German orientation when it came to his science policy, and he often cited the German example, the minister actually wanted to extend his characteristic efforts in cultural diplomacy beyond Germany. Klebelsberg traveled willingly and often for this end. He writes about the continuous and, for him, natural German connections that we referred to above: “I am off to Germany, where Prussian Minister of Culture, Becker, a great friend of Hungary, will show me willingly the newest cultural institutions of the Prussian state. This is the most direct and greatest support he could extend to us” (Klebelsberg 1930, 46). Besides these German visits, he also travelled to and gave lectures in Italy and Austria on a few occasions. In 1930, he conducted a “Northern trip”, visiting Stockholm, Turku, Helsinki, and Tartu, attending and giving speeches in various congresses. The final destinations of his travels were Riga, Vilnius, and Warsaw. The benefits of these visits were the reinvigoration of international cultural relations and exchange programs with these countries, especially aimed at joint historical, linguistic and folkloric research. He was not the only one to travel extensively, Prime Minister Bethlen also made a number of visits for cultural diplomatic reasons. He writes the following about this in Pesti Napló: “There are many direct and indirect benefits of Bethlen’s successful visits to Rome, Lord Rothemere’s press relations, Minister of Culture Becker’s last-year visit to Budapest, and the planned Hungarian visit of Italian Minister of Education Fedele” (1927, 109). He claims that the most important effect of these visits is that they can strengthen national optimism and faith in the future. These mutual visits create the image that Hungary is indeed an important part of European cultural and academic life, since it has great significance that Italian scientists praised to him “the spectacular biochemical research in Budapest’s Korányi Clinic”. The Secretary’s visit from the Italian Ministry of Education contributed to the success of acquiring the Falconieri Palace in Rome, in which the Collegium Hungaricum was established (Klebelsberg 1928, 60, 71, 109).

Naturally, when examining Klebelsberg’s efforts in cultural diplomacy, we need to consider its close connection Hungary’s general foreign policy efforts in this era. The task was not only to keep up with the international cultural competition of the 1920s, but also to remedy the diplomatic isolation of Hungary after Trianon. The closest relations were maintained with the states that remained in contact with Hungary during its almost complete isolation at the beginning of the decade. Nonetheless, Klebelsberg endeavored to extend the country’s relations by forming new connections and disseminating the results of Hungarian cultural achievements. It was his firm belief that by eliminating cultural isolation, diplomatic isolation would cease as well. The minister thought that it was not coincidental that Western European countries and the United States were leading scientific development efforts, and thus, their example must be followed – especially that of the latter. He disagreed with those who acknowledged US economic supremacy at the time, but saw European culture and science as more developed. He strongly believed that “the political center […] was relocated to the other side of the globe, [and] the intellectual influence exerted by the American branch of English culture is felt more and more: America is catching up quickly in the cultural race to the leading nations of Europe” (Klebelsberg 1930, 213-215).

Klebelsberg did not conceive of and realize cultural diplomacy solely through politicians: he considered prominent scientists, university professors, and artists to be ambassadors of Hungarian culture, who can promote Hungarian cultural achievements in leading European states, such as Germany, Austria (as an independent country until March, 1938), Italy, France, and England. “This is how we dismantle that great wall separating us from Europe” – wrote Klebelsberg with joy and pride about his plans, efforts, and results in Pesti Napló in 1929. “Twenty-five Hungarian university professors visited Breslau, where they were lecturing, operating, and experimenting for a week as part of the curriculum. A similar delegation from Breslau will arrive to us in return next fall” (1929, 221). He elaborates on the fact that this event, cause for pride on its own, is part of a larger, continuous and coordinated effort to “make the absolute values of Hungarian culture known to the European public” (1930, 74). He also writes about the successes of the second “Hungarian Week” in Germany. At the beginning of the year, a representative series of Hungarian fine art exhibitions took place in Nuremberg, with concerts by the singers and musicians of the Budapest Opera House. At the same time, archeologists and art historians were on an extensive, successful visit to Berlin (1930, 87-89). These successes were the result of relentless work, which had its antecedents, but 1929 was beyond doubt the year of successes in Germany. However, Klebelsberg summarized his aims in the previous year, at that time, regarding sports diplomacy. “The art expo in Rome and the Amsterdam Olympics were marvelous opportunities to let the international public know about our cultural significance. The success of our painters and sculptors in Rome, and that of our fencers in Amsterdam are all testaments to a Hungarian truth” (1929, 37). There are countless other examples, as well.

It is certain that not all of Klebelsberg’s lofty visions were realized. This was in part due to the many, sometimes diverging interests within the government, the slow disintegration of the fragile postwar order, and the limits of Klebelsberg’s own capacities. However, it is evident from his plans – both realized and unrealized – that his Western orientation was dominant in his cultural diplomatic vision. This admiration of the West, stemming, as mentioned, from his own background and schooling, was evident in his wishes to integrate young Hungarian academics and intellectuals into the stream of European academic life – which can be seen as yet another pillar of his cultural diplomacy.

Collegium Hungaricum and Scholarships

Klebelsberg intended to establish Hungarian institutes in foreign countries to become the cornerstones of his efforts in cultural diplomacy. He devoted incredible amount of time, energy, and considerable funds to create a network of these institutes and a related system of scholarships. “It is quite obvious that our political standing can only be improved if our general international perception improves as well. Hungarian cultural institutes in foreign countries will also serve this aim […]” (Klebelsberg 1928, 107). Hungarian cultural policy had to be connected to the international scientific community in Klebelsberg’s view, because there was a long tradition of exchange programs, from medieval peregrinates to the scholarships of the dualist monarchy, which he knew very well, and referred to often in his writings. These institutes were intended to serve a diplomatic purpose too, as he was convinced that “new political relations shall be established with a Collegium Hungaricum” (Klebelsberg 1930, 75). Klebelsberg frequently used the argument that such institutes were long maintained by other nations, such as France and England, in Athens and Rome. He thought that these institutes were seen by the home states not merely as research institutions, but as able instruments to enhance international intellectual cooperation (Klebelsberg 1927, 188-189).

The Ministry of Culture proposed legislation in 1927 to formally reinforce the formerly established institutions collectively called Collegium Hungaricum, as well as a related system of scholarships through which professors and students could travel abroad.5 The most significant of these institutes were in Berlin, Rome, and Vienna; these were intended to strengthen the already close diplomatic relations with the host countries, and had predecessors before Klebelsberg’s time in office, but their new, representative buildings were acquired through this legislative action.6 Klebelsberg had considerable impact on these institutions, bringing in a more professional and centralized control over them. Compared to institutions maintained by other countries, the primary aim of these was to serve as “headquarters” for elite training, to help professors and students study and conduct their research in the respective countries. In addition to this, the institutions also promoted and disseminated Hungarian culture in the host country. “[The institutes] have a two-fold purpose. They host the best of our college graduates, who can perfect their knowledge under the most renowned professors of their fields in these centers of world culture, and also easily acquire the language of the host country. But each Collegium has an academic department with esteemed representatives of Hungarian academic life as their heads, who can gain the confidence of statesmen in these countries and form fruitful social and intellectual relations” (1928, 108).

Klebelsberg saw this structure important with a view to nurturing young artistic and academic talent. “The model of these Hungarian institutes will be at the intersection of a boarding school and a research center. It will be beneficial for the visiting student to live among their peers and also young researchers and scholars from their home country. In those cultural hubs, where there is a considerable artistic scene, artistic departments will also be established”, claimed Klebelsberg in his comment accompanying the legislation (1927, 443). He poses the question while arguing for the scholarships: “What are the ways to successfully connect to the West nowadays? We must send a large number of Hungarian graduates to study abroad” (1927, 639). However, this aim was hindered by the relatively low language attainment of the students, which is, of course, the prerequisite of successful international cooperation. Thus, Klebelsberg carried out his secondary education reform with the aim of enhancing language teaching, introducing the teaching of modern languages, which was a problematic issue due to the low number of qualified teachers. “My concept is built upon the successful acquisition of two modern languages, and it can only work in real life if the schools have adequate teachers of English, German, French, and Italian, with proper language use and pronunciation” (1927, 574). Therefore, he also designated a role for these institutes concerning language teaching in secondary schools , but, as mentioned, the current teaching staff was often undertrained for such tasks. “Not due to their own fault, but a number of our teachers working in secondary education do not yet have the capacity to teach modern languages, since it was not before a requirement. This is the reason for the relatively low attainment of secondary school students in language learning. Thus, it is a primary goal to educate teachers of English, French, German, and Italian in these institutes. This was the first step of our endeavor, as I have sent many prospective teachers of these languages to the respective countries, so they can serve modern philologists as soon as possible” (1928, 22).

In certain countries, where it was possible to establish a Collegium Hungaricum, cultural diplomatic relations were maintained in other ways; in many cases with libraries, university departments, or lector offices. Such institutions were in operation in Sofia, Stockholm, Munich, and Helsinki. Moreover, Klebelsberg founded a minor Hungarian institute in Warsaw. Due to financial difficulties caused by the economic depression, they could not open – contrary to plans – a proper Collegium Hungaricum in Paris. In England, Klebelsberg was exerting his diplomatic influence in order to establish the proper conditions for the prospective teacher’s education program.

Klebelsberg had grand plans for these colleges, often following the good practices of countries with more established, independent academic traditions. During the legislative debates of the 1924 Hungarian state budget, he was praising his partners in this effort: “I have to thank here specifically the University of Oxford, where there was a special warm welcome to Hungarian students, and the Protestant university in Aberdeen, where they were uncharacteristically welcoming towards those students who are to teach English language and literature in Hungarian Protestant schools in the future. Similarly, with the much-appreciated help of the Archbishop of Westminster, the St. Edmund House in Cambridge received the future professors of Hungarian Catholic orders, so that they will have the proper education to teach English language and literature in Hungarian schools maintained by these orders” (Klebelsberg 1927, 573). Klebelsberg deeply believed in this idea. He personally organized preparatory meetings for the recipients of these scholarships before their departure, so that their time is spent the most efficiently. “As much as I can, I want to prepare these delegations on an institutional level. Within the framework of the Horthy-college, we will establish three separate houses: a German, a French, and an English one, where the prefects are the teachers coming here from Germany, France, and England. As a result, the selection and preparation of our children to be sent abroad will happen more efficiently and on a larger scale than now. There’s no denying, it took a great deal of personal effort on my behalf these past years to put together teams of students that we can confidently send abroad” (Klebelsberg 1927, 554).

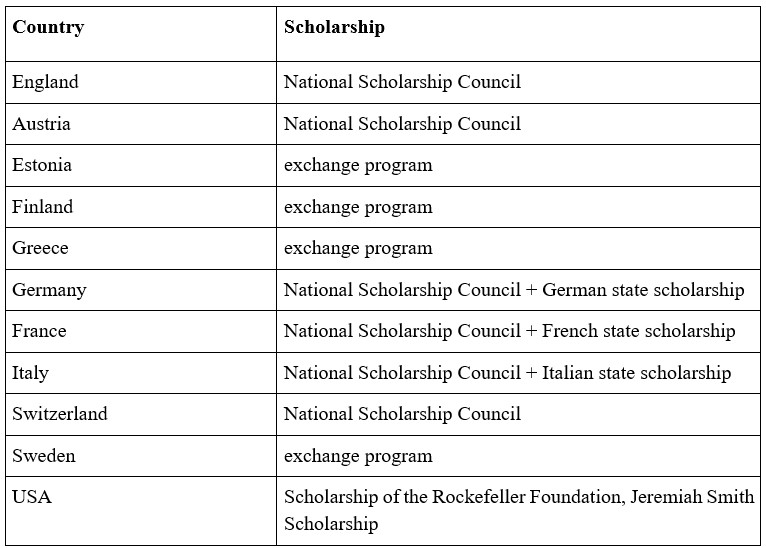

§3 of the aforementioned legislation established the National Scholarship Council, the task of which was to manage and distribute the international scholarships provided by the Hungarian state. The Council was handling scholarships on an organizational and legal level, and also provided a strict professional set of objective criteria for assessing the applicants. (Ujváry 2010, 137-138). Besides these, there were scholarships to Hungarian students by offered foreign states (e.g. to Paris), and international exchange programs (e.g. to Greece and Finland). Klebelsberg also obtained scholarships from the Rockefeller Foundation to the USA, and for engineers, the Jeremiah Smith Scholarship provided opportunities (Rapali, 124).

The scholarship opportunities that Klebelsberg was aware of and referred to in his speeches are summarized in the following table:7

It is important at this point to discuss Hungarian relations with the Rockefeller Foundation at this time. Klebelsberg was exceptionally enthusiastic: “In England and America, the officers of the Rockefeller Foundation are establishing research funds – these are truly the most modern politicians of science!” (1931, 95). He even places them in a cultural historical framework: “After the First World War, there was a gap in European cultural policy, filled by the large-scale help on behalf of America. In global science policy, it was the Rockefeller Foundation that took initiative, establishing a large number of research institutes and providing funds for young academics, in order to save the perishing culture of Europe” (Klebelsberg 1931, 96). Klebelsberg was eager to seize this opportunity and negotiated extensively about the scholarships and other possible forms of support with the representatives of the Foundation. “One of the leading executives of the Rockefeller Foundation, a certain Mr. Rose, with whom I have had long talks, showed considerable understanding towards our efforts. At this very moment, there are six young mathematicians, chemists, physicists and biologists working abroad with the help of the Foundation, and they are so appreciated that the Foundation has decided to increase the number of possible recipients up to ten in the following year” (Klebelsberg 1927, 640). That “certain Mr. Rose” Klebelsberg mentions passingly is none other than the founding director of the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission (1909) and later of the Foundation’s International Health Commission, Wicliffe Rose, a champion of public hygiene and sanitary health during the 1910s and 1920s in the United States (Page 2002, 266). Rose himself mentions his visit to Hungary, “to offer fellowships at his discretion”, in his journal entries in March, 1922. Since there are no other sources indicating when and how Klebelsberg came into contact with the Rockefeller Foundation, this spring visit in 1922 may very well be the first point of contact between the Foundation and the Hungarian cultural state apparatus. Rose’s visit were part of his larger initiative towards Central Europe, as he had made extensive visits to the newly-formed state of Czechoslovakia, Poland, Austria before arriving in Hungary (Page 2002, 277).

Furthermore, it is important to mention the efforts of Jeremiah Smith, Commissioner-General of the League of Nations loan to Hungary in 1924, who established a foundation using his personal salary to fund American scholarships for prospective Hungarian engineers. From 1927, the foundation provided three scholarships annually, the discontinuation of which is unknown due to the lack of sources (Huszti 1942, 157).

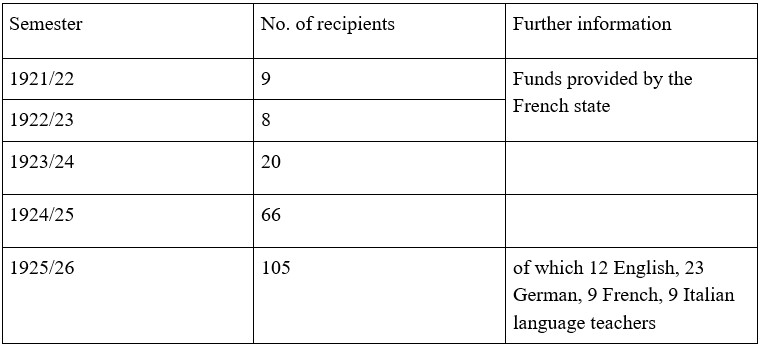

Klebelsberg was also very appreciative of the fact that young researchers had opportunities to visit not only the United States, but also other European countries. The selection process of the scholarships was carried out in cooperation with the National Scholarship Council, which was important for Klebelsberg, as he saw it as a chance to maintain cooperation between his Ministry and the Foundation. “I was overjoyed by the news that as a continuation to our current programs, the Rockefeller Foundation provided a further $18.000 to the National Scholarship Council, established by Act XIII of 1927, as an autonomous organization, to support study visits to the United States. Usually, the Foundation retains the rights to make decisions about the recipients, with the exception of only three organizations, one of which is our own Council. Thus, there is a proper, institutional connection with American universities and research institutes, which is to be maintained with care on our behalf” (Klebelsberg 1930, 218). It is worth summarizing the number of scholarship recipients, as they are showcasing a clear tendency of Klebelsberg successfully implementing his vision.8

Although these achievements are quite astounding in view of contemporary financial and infrastructural possibilities, there was a considerable and acknowledged sense of elitism when it came to the recipient of these scholarships, with a clear lean towards the middle class: “The international scholarships and especially the Hungarian institutes will open the way to the educated West for the most talented children of the Hungarian middle class. This is the social policy significance of these Hungarian cultural institutes” (Klebelsberg 1928, 18). Other, especially lower social classes are not mentioned by the article.

A considerable amount of the Ministry’s budget was devoted to the establishment and maintenance of various cultural institutions around Europe. The largest items on the budget list were, however, the purchase and renovation of the new palaces in the three representative capitals, since Klebelsberg was convinced that these buildings had to represent the greatness of Hungary. He was attacked vigorously for this prodigality, but he carried out his plan nonetheless, for which he needed the support of Prime Minister Bethlen. Notwithstanding this criticism, he strove to convince the public and justify his spending. He acknowledged in several pieces that he was fully aware of the country’s economic hardships, but that “there is hardly any more important field on which this money could be spent” and that “these institutes, by connecting with the prominent intellectual forces of the host countries, will simply transform the image of Hungary and its values in the eyes of these nations” (Klebelsberg 1928, 18, 26).

As a symbolic culmination of his efforts in these areas, he offered a department chair to Albert Szent-Györgyi at the University of Szeged in 1928, who was also a recipient of a Rockefeller scholarship, pursuing research in Cambridge in 1926, and who was to have an important role in Klebelsberg’s concept of Hungarian academic life. Although Szent-Györgyi asked for some time to finish his research, he took the position in Szeged in 1931. The development of the laboratories in Szeged was also supported by the Rockefeller Foundation. In 1931, the University received $119.000 from the Foundation, with an option for further funds in the years to come. Klebelsberg could not know at the time — and did not live to see it — that Szent-Györgyi’s research will be awarded with the Nobel Prize, but his well-structured and prescient cultural diplomacy and modern science policy contributed vastly to this shared national success.

In sum, it is clear that in the context of the postwar situation and the contemporary political, financial and infrastructural conditions, Klebelsberg did all he could for the development of Hungary’s international standing through cultural diplomacy, and his modernizing, Western-style policy of science was successful. His public and private records all mirror a sense of nationalism that was distinct from many of his contemporaries; that rejected backwardness and provincialism, and saw the way out from the national catastrophe of Trianon not in the closing of the Hungarian mind, but its opening. His international renown, his science policy, his influence in the diplomatic life of the era, and his higher education policy were evidence for his wish for practical, material results based on these premises. For better or for worse, this orientation was one of the defining features of the Horthy-regime in its first decade, which has to be considered when assessing it in its entirety. Historical memory tends to enlarge or minimize such elements, and view statesmen and their age through the prism of the present – whereas for a fuller, better understanding, it is primarily the nuances that need to be considered. Only through the lessons of these nuances may we hope to understand the present and shape the future.

Works Cited

Primary sources

- KLEBELSBERG Kuno. 1927. Beszédei, cikkei, törvényjavaslatai. [Speeches, Articles, Law Proposals] Budapest: Atheneum.

- KLEBELSBERG Kuno. 1928. Neonacionalizmus. [Neo-nationalism] Budapest: Atheneum.

- KLEBELSBERG Kuno. 1929. Küzdelmek könyve. [Book of Struggles] Budapest: Atheneum.

- KLEBELSBERG Kuno. 1930. Jöjjetek harmincas évek. [Come, 1930s!] Budapest: Atheneum, 1930.

- KLEBELSBERG Kuno. 1931. Világválságban. [In World Crisis] Budapest: Atheneum.

- GLATZ Ferenc ed. 1990. Tudomány, kultúra, politika Gróf Klebelsberg Kuno válogatott beszédei és írásai. [Science, Culture, Politics: Selected Speeches and Writings of Count Kuno Klebelsberg] Budapest: Európa.

- HUSZTI József. 1942. Gróf Klebelsberg Kunó életműve. [The Œuvre of Count Kuno Klebelsberg] Budapest: Magyar Tudományos Akadémia.

Secondary sources

- ABLONCZY, Balázs. 2016. Keletre, magyar! A magyar turanizmus története. [To the East, Hungarians! The History of Hungarian Turanism]. Budapest: Jaffa.

- KOVÁCS M. Mária. 2011. Numerus clausus Magyarországon, 1919-1945. [Numerus Clausus in Hungary, 1919-1945] In: Molnár Judit ed. Jogfosztás – 90 éve: tanulmányok a numerus claususról. [Disqualification – 90 Years: Studies on Numerus Clausus] Budapest: Nonprofit Társadalomkutató Egyesület.

- MIKLÓS Péter ed. 2008. A legnagyobb álmú magyar kultuszminiszter – Klebelsberg Kuno kora és munkássága. [The Cultural Minister with Grand Dreams – The Age and Work of Kuno Klebelsberg] Szeged: Belvedere Meridionale.

- MIKLÓS Péter. 2003. “Az egyházmegyei központ kiépítése Szegeden 1923–1941.” [The Creation of the Ecclesiastic Center in Szeged 1923-1941] Egyháztörténeti Szemle 286–99.

- MOLNÁR Miklós. 2001. A Concise History of Hungary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ORMOS Mária. 1998. Magyarország a két világháború korában. [Hungary in the Age of World Wars] Debrecen: Csokonai.

- PAGE, Benjamin B. 2002. A Reconsideration. Minerva 40, no. 3:265-287.

- ROMSICS Ignác. 2005. Magyarország története a XX. században. [History of Hungary in the 20th Century] Osiris, Budapest.

- RAPALI Vivien. 2017. A Smith Jeremiás Ösztöndíj története [The History of the Jeremiah Smith Scholarship] In: Illik Péter ed. Különvélemény [Minority Report] Budapest: Unicus Műhely Kiadó.

- SZINAI Miklós-SZŰCS László ed. 1972. Bevezetés [Introduction] In: Bethlen István titkos iratai. [The Secret Papers of István Bethlen]Budapest: Kossuth Kiadó.

- T. MOLNÁR Gizella. Változások Szeged kulturális életében az 1920-as években [Changes in the Cultural Scene of Szeged in the 1920s] In: Blazovich László ed. 1997. Tanulmányok Csongrád megye történetéből XXIV. [Studies in the History of Csongrád County] Szeged: Csongrád Megyei Levéltár.

- UJVÁRY Gábor. 2009. Klebelsberg Kuno és Hóman Bálint kultúrpolitikája. [The Cultural Policy of Kuno Klebelsberg and Bálint Hóman] In: Romsics Ignác ed. A magyar jobboldali hagyomány. Budapest: Osiris.

- UJVÁRY Gábor. 2014a. “Egy európai formátumú államférfi”, Klebelsberg Kunó (1875–1932). [“A Statesman of European Standing – Kuno Klebelsberg (1875-1932)] Pécs-Budapest: Kronosz Kiadó – Magyar Történelmi Társulat.

- UJVÁRY Gábor. 2010. A harmincharmadik nemzedék – Politika, kultúra és történettudomány a „neobarokk társadalomban”. [The 33rd Generation – Politics, Culture and Historical Studies in the “Neobaroque Society”] Budapest: Ráció Kiadó.

- UJVÁRY Gábor. 2014b. Kulturális hídfőállások – A külföldi intézetek, tanszékek és lektorátusok szerepe a magyar kulturális külpolitika történetében I. – Az I. világháború előtti időszak és a berlini mintaintézetek. [Cultural Bridgeheads – The Role of Foreign Institutes, Departments and Lectorates in the History of Hungarian Cultural Diplomacy I. – The Era before World War I and the Institutes in Berlin] Budapest: Ráció Kiadó.

- UJVÁRY Gábor. 2017. Kulturális hídfőállások – A külföldi intézetek, tanszékek és lektorátusok szerepe a magyar kulturális külpolitika történetében II. Bécs és a magyar kulturális külpolitika. [Cultural Bridgeheads – The Role of Foreign Institutes, Deparments and Lectorates in the History of Hungarian Cultural Diplomacy I. – Vienna and the Hungarian Cultural Diplomacy] Budapest: Ráció Kiadó.

Notes

1 The Law XXV of 1920 did not directly target Jewish university students, but their proportion in higher education dropped dramatically from 30% to 8 % as a result. Although with the 1928 modification, this number rose to 12%, the anti-Semitic nature of the law remained prevalent. ↩

2 All translations were done by the authors. ↩

3 For his collected writings, see Works Cited. ↩

4 Medical researcher, pathologist, microbiologist, and immunologist. He and his institute are known for pioneering a number of Hungarian preventive measures, including the introduction of vaccination against diphtheria, stopping the spread of typhoid fever, organizing the struggle against tuberculosis on an institutional level, and the creation of a protective system for mothers and infants in Hungary. In this paper, we do not wish to contribute to the debate about his person emerging in the first half of the 2000s. For more, see: https://web.archive.org/web/20181118164650/https://mno.hu/migr_1834/johan-bela-teljes-arckepehez-718587 ↩

5 Law XIII of 1927. ↩

6 For an in-depth analysis of Hungarian cultural institutes abroad, see Ujváry 2014b, 17. ↩

7 Compiled by the authors based on Klebelsberg’s parliamentary speeches and accounts in Klebelsberg 1939. ↩

8 Data is gained from Klebelsberg’s papers and from his account during the aforementioned budget debate. ↩

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.