1. Anger and American society

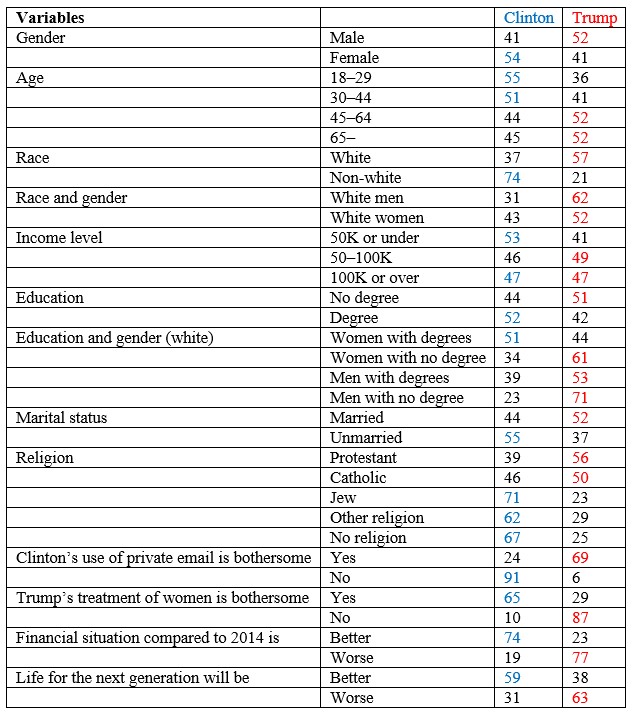

The 2016 election of Donald Trump to the US presidency has been studied from numerous angles, including voter demographics in terms of gender, race, class, age and educational level, among other factors. Based on exit polls (Figure 1), it was soon established that Trump was put into office by white voters – mainly men, but also a surprisingly high number of women; by members of the lower and middle classes (Draut 2018, 11–12) – but also by members of the upper class; by people without a college education – but by many with degrees as well; and by people over 45 – but also by many younger people. Trump voters tended to be married and Christian by faith, and they came from rather more traditional and conservative layers of American society.

Exit poll findings, fine-tuned to reflect not only the most basic categories of gender, race, religion, etc. in terms of voting behavior, but also processed data that measures at least two variables at once, presents us with a much more nuanced set of results – and portrayal of American society. Days after the election in 2016, Junn (2016) published an article in which she points out that, indeed, men voted for Trump and women for Clinton, but if we also consider the racial distribution along with gender, it becomes clear that the majority of white women voted for the Republican candidate. Moreover, she continues, data from the National Election Study reveals that since 1952, the majority of white women have consistently supported the Republican Party and voted for the Democratic candidate only twice: in 1964 and 1996 (see also Frasure-Yokley 2018, 4–5). A further division of this group based on educational level – which is often used as one marker of class, even though the social landscape has been changing in this regard (see Standing 2011) – demonstrates that, actually, white women with degrees comprised the only segment among white voters that cast the majority of votes for the Democratic candidate (51%). Still, the simple fact that remains in the public mind is: American men voted for the Republican, and American women voted for the Democrat.

Both Yarrow’s description of “sidelined men” or “men out” living on the margins of American society, “disconnected from work, family and children, civic and community life, and relationships … often angry with government, employers, women and the ‘system’” (2018, xii) and Kimmel’s study of “angry white men,” deeply fueled by “the potent fusion of two sentiments – entitlement and a sense of victimization” (2017, x), that is, experiencing “aggrieved entitlement,” capture the essence of the large white male population that was attracted to Trump and what he symbolized. They voted with their hearts: their emotions of disappointment, their sense of deprivation, their disillusionment and hopelessness, which culminated in rage. In Trump, they recognized the man who understands them, feels their pain, speaks their mind and can truly represent them: the white men who used to be the heartbeat of America.

In the context of the US, the frustration of white men on the structural level is the outcome of a longer series of crises, the beginning of which I would relate to the social changes of the late 1950s and 1960s, when a succession of political upheavals, from the protest movements to end racial segregation and discrimination, through the women’s movement, gay movement, students’ movement, anti-Vietnam movement and hippie movement to the Fourth Great Awakening, shook the nation and its traditional, gendered and racially segregated, patriarchal, heteronormative and Christian foundation. Kimmel, on the other hand, in his history of American masculinities (2012), locates the emergence of angry white men in particular in the 1990s, when they started to portray themselves as victims of American society. As Wiegman points out, they mobilized “the language of the civil rights … to protect whiteness, which is cast not only as a minority identity but also as one injured” (1999, 116). By drawing on the political logic of the civil rights era, they engaged in discourses of victimization in terms of both race and gender and were thus able to challenge public practices of “reverse discrimination” instituted by affirmative action programs. 9/11 added further challenges to traditional masculinities as it represented an attack on the body of the nation, stirring up enormous frustration and anger in many. The recession that evolved out of the housing crisis in 2008 placed a series of further burdens on many of America’s men, who felt continually disenfranchised, humiliated and beaten, even though, as far as they could see, they had done nothing wrong (see Annus 2015). This sense of undeserved victimhood surfaced among white men in particular, of all socio-economic standings and increased their frustration, dissatisfaction, worry and anger.

Anger in particular has been recognized as an increasingly important indicator that impacts people’s political behavior.

"Anger has a peculiar power in democracies. Skillfully deployed before the right audience, it cuts straight to the heart of popular politics. It is attention-getting…. It is inherently personal and thereby hard to refute with arguments of principle; it makes the political personal and the personal political. It feeds on raw emotions with a primal power: fear, pride, hate, humiliation. And it is contagious, investing the like-minded with a sense of holy cause." (Freeman 2018)

And the “politics of outrage” is the essence of the current presidency, as Freeman (2018) notes in her analysis of the Brett Kavanaugh case, also reflecting on how this is not the first time this has happened in US history: the politics of anger also dominated the period of the 1830s to 1850s, paving the way to what then became the greatest test of the union. Traister discovers a more generic power in anger when claiming that, broadly speaking, it “has often been the sparkling impetus for long-lasting, legal or institutional reform in the US” (2018, xxiv), but also observing that, at the same time, Americans “have never been taught how noncompliant, insistent, furious women have shaped … history” (xviii), as their anger has “often been vilified or marginalized” (xxiv).

After the electoral vote put Trump in the presidency – despite Clinton having won the majority of the popular vote – the streets of big cities were flooded with protestors, among them many women, who refused to acknowledge Trump as their president, culminating in the “Not My Presidents’ Day” rallies held nationwide on February 20, 2017. The greatest demonstration of American women’s anger and frustration about continuing social inequalities and injustices, however, was the Women’s March, held on January 21, 2017, the very first day after Trump was inaugurated. It was reported to be “the largest day protest in US history,” with the number of marchers estimated to fall between 3.3 and 4.6 million, rounded out by another 300,000 sister marchers in other cities worldwide (Broomfield 2017).

2. Anger and women in American culture

Traditionally, American cultural perceptions have recognized anger as a masculine feature, with certain forms being associated with particular class or race/ethnicity. Mid-nineteenth-century constructions of true womanhood expected submissiveness and piety in proper, read up-and-coming, white middle-class women, while anger signified a potential emotional transgression of the trope of the angel of the house: the ideal woman, daughter, wife and mother. And women who failed to comply were singled out either as the madwoman in the attic, hysterical and not in control of her emotions and intellect, or the fallen woman: women of color, of the lowest income, and with an active interest in transforming society which could be implemented only via the public realm, reserved for men primarily: suffragists and women in the social gospel movements who acted upon their religious zeal to fight social evils as the angel of American society as a whole.

This is reflected in recent American popular perception, as women’s public display of anger seems to have been structured along three dimensions: (1) political preferences, such as liberal-minded women being associated with women’s rights activism, fighting against causes linked to specific conditions resulting from persistent gender inequalities in society, such as the # Me, too movement; (2) religious convictions, such as deeply pious women fighting against abortion, which they perceive as an act of legalized murder; and (3) racial experiences, epitomized by the trope of the angry Black woman used to nullify the experience of aggression they face regularly (hooks 1992, 120), which surfaces even in some of the representations of former First Lady Michelle Obama (Kovacs 2018). Black women, however, exploited this stereotype in the hope of subverting the systematic oppression responsible for its original construction by reclaiming this trope either to create their own intersectional academic voice – as illustrated by, for example, the oppositional gaze (hooks 1992) and Black feminist autoethnography (Griffin 2012) – or to claim visibility for Black women’s experiences, such as by initiating the #Black Girls Matter project in New York City or the #Say Her Name movement.

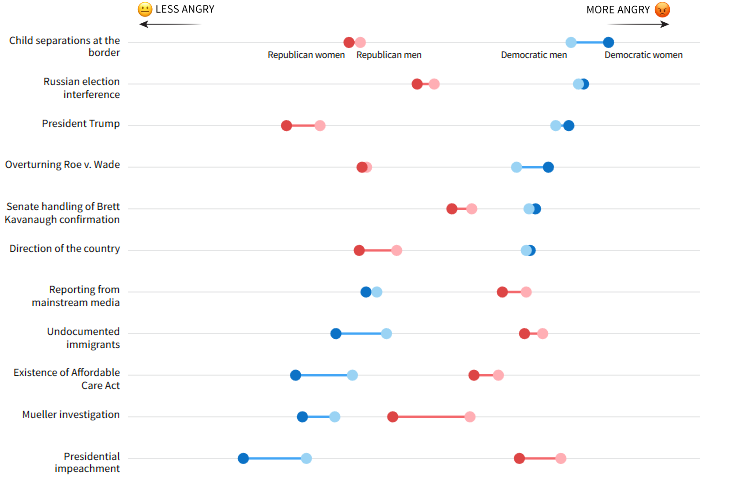

Statistics, however, seem to indicate that anger impacts the lives of most women in the US today. As an acknowledgement of the evolving public power of anger, the Pew Research Center made anger a regular item in their polls on emotions in 1997. The pattern that emerges from their data indicates that Americans are growing angrier each year: at the end of 2017, they found that 24% of the Americans they asked were angry, 55% were frustrated, and only 13% were content (Bowman 2018). CNN (2016) polls taken a year earlier had similar results but also demonstrated a significant difference between men and women. Data indicated that women’s anger was “more intense”: 37% claimed that they are very angry, as opposed to 25% of men. Then elle.com reported in their 2018 survey that among white women, “79% report rage-fueling news encounters at least daily” (Harris-Perry 2018). This high number suggests women’s emotional investment and disillusionment in current affairs, regardless of their political affiliation and voting preferences. A survey by Reuters and Ipsos conducted between August and October 2018 (Figure 2) measured the public emotional response to some of the most controversial issues and found marked differences based on gender, age, party affiliation, educational level, etc. (Still, Kahn and Smith 2018).

In parallel, an ever-growing number of studies has also reported on the anger of women, some of which surveyed anger among traditional white American women, typically identifying with particular ideologies, such as white supremacy or the alt-right, and their respective groups, such as the Ku Klux Klan. In her landmark volume Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s (2009), Blee revisits the female auxiliary group of the KKK established during its second revival and demonstrates how thoroughly integrated their extensive operation was into the Klan. Her volume Inside Organized Racism: Women in the Hate Movement (2002) studies women in white supremacist hate groups through ethnographic interviews she conducted in various parts of the country. These groups have been mushrooming all over the US: Kimmel reports that in 2017, for example, the number of active hate groups was 917 (2018, xi). In Healing from Hate: How Young Men Get Into – and Out of – Violent Extremism, he (2018) also studies some of these hate groups and argues convincingly for the highly gendered nature of extremism, which he sees as being fueled by the politicization of an overall sense of emasculation and humiliation in the US, experienced both in the public and private realms, by men and, through them, by women as well. In her recent volume Mothers of Massive Resistance: White Women and the Politics of White Supremacy (2018), McRae charts segregationist and conservative white women’s association with the white supremacist movement throughout most of the twentieth century, tracing the trajectory of their massive resistance in relation to social movements and federal legislative steps to advance racial equality. In Righting Feminism: Conservative Women and American Politics (2008), Schreiber investigates how conservative women have attempted to organize themselves since the suffrage movement in a bid to gain national political currency to fight for issues close to their hearts, while Gorman, through an autobiographic piece entitled Growing up Working Class: Hidden Injuries and the Development of Angry White Men and Women, unveils how “hidden injuries of class frustrate and anger the working class, including many working-class women (a fact that is often overlooked)” (2017, 6), and demonstrates how various economic as well as ethnic/racial and social changes account for these.

3. Angry tradwomen of America

But what accounts for the fury of traditional American women who support the GOP? After eight years of a Democratic presidency, they have their candidate in office – why are they not content or pleased? Why don’t they trust in the future they envisioned though his leadership? What follows is an investigation of a series of studies as well as of various articles, interviews and online content conducted in the hope of unveiling who these angry white traditional women on the conservative side of the political spectrum are and why they continue to be fueled by anger. In the process, I rely on content analysis of interviews and case studies in Blee (2002), Schreiber (2008), Kimmel (2018) and Gorman (2018). I also examine online programs by Lana Lokteff, possibly the most influential alt-right woman in the US today, along with some online content and two documentaries by Lauren Southern, a libertarian and identitarian, former right-wing activist, journalist and internet personality, one of the “white power Barbies, … a new cohort of glamorous far-right female influencers [who] have become unlikely ‘role models’ for young women on social media, promising heaps of male attention, luxury lifestyles and the chance to join sisterly ‘communities’ where they can get dating advice” (Evans 2019). In addition, I also look at the online presence of Ayla Stewart, another white supremacist commentator, a former Latter-day Saint and mother of six, who goes by the expressive name “Wife with a Purpose.” Although both Southern and Stewart retired from public activities in 2019, their online content has resonated with their followers in the hundreds of thousands, whose comments reflect views shared by many tradwomen. Tellingly, much of their – and Lokteff’s – internet content has since also been removed.

One effective way to approach the complexity of concerns and fears that have been feeding into this anger is intersectionality, which “highlights the need to account for multiple grounds of identity when considering how the world is constructed” (Crenshaw 1991, 1245). Crenshaw’s model enables us to recognize the intricate web of experiences through which these women share in feeling the erosion of their privilege, which they experience as a gradual shift from the center – something that leads to their status anxiety, eventually evolving into rage. The pattern that took shape before my eyes may thus be mapped on the basis of identity segments that (1) intersect within the family unit – after all, as Collins (1998) claimed, it is all in the family – and (2) reflect non-egalitarian social categories and ideologies, which have operated as pillars of traditional privilege, amongst them whiteness, Protestantism, patriarchy, (hegemonic) masculinity and class status. The intersectional approach assists us to disclose how these operate through an interlocking system of privilege and we may detect how negative change within one field impacts other areas as well. This group of women, referred to by the umbrella term as tradwomen, includes traditional women who have been voting GOP, are white, range from proud American patriots all the way to white supremacists, from conservative to alt-right, in the middle or lower class, typically religious, family-oriented tradwives and tradmoms, who have been disappointed with the political establishment as well as the socio-economic changes and challenges they have been facing. What follows is a presentation of some of their specific concerns that shake the pillars of their identity and position, causing doubt, fear and anger in them day after day. While these concerns systematically intersect, they will be thematically discussed along the broader topic of politics, race, class, religion and gender.

3.1. Politics

As far as politics and the presidency are concerned, a most potent theme for tradwomen seems to have been the flow of constant attacks on Donald Trump, both in the streets and through “fake news” in the media, all of which have culminated in efforts among anti-Trump forces to impeach the president. As the hearings were unfolding, the outrage was increasing. Many women, from mainstream conservative to the alt-right, supported Trump because they recognized him as someone who is not from the inner circles of Washington and thus is able to shake up the establishment, which they resented for having deserted them. Tradwomen portray their world as unfair: they maintain that they have been deprived of what had “rightfully” been theirs and perceive the federal government as having misused its power when forcing them “to embrace multiculturalism,” as Ayla Stewart notes (Gordon 2018), along with feminist conceptualizations of women’s equality. These are seen as signs of the establishment attacking the traditional white family model, which is constructed in their discourse as “victimized, at risk and requiring protection” (Gordon 2018). In addition, they are also troubled by the recurring debate about gun control as it is thought to threaten their constitutional right and ability to protect themselves and their remaining property if needed.

Some studies also investigate how the Republican Party in particular is perceived as having failed to represent tradwomen’s concerns, thus explaining why these women supported Trump’s candidacy within the party. Schreiber (2008) analyzes some of the key moments of the efforts through which conservative women have been fighting for political representation and investigates how, with the lack of proper party representation, they established two organizations to assist them in achieving their aims. The group Concerned Women of America (CWA), established in 1979, is active in promoting 1) the sanctity of life in a number of areas, thus opposing birth control, abortion and any form of stem cell research and gene modification procedures; 2) home schooling, in order to avoid segregation, school violence and the impacts of secularization; 3) the nuclear family model, and therefore marriage and heteronormativity; and 5) freedom of religious practice (Schreiber 2008, 27). The other group, called the Independent Women’s Forum (IWF), was established in 1992 “to transform debates about ‘women’s’ issues by offering the viewpoints of conservative women” (Schreiber 2008, 13). It lists among its priorities the fight regarding violence against women, the harmful effects of the internet, birthright citizenship and women’s issues in healthcare and the workplace (Schreiber 2008, 27). The scope of both organizations also reflects current concerns that continue to upset and anger tradwomen.

These organizations, however, still fail to represent everyone on the right: women embracing more off-center, right-wing ideologies, such as white nationalism, paleoconservativism and alt-right views, still find themselves outside of Washington circles. The ideological divide persists, as Critical Condition, a right-wing vlogger, pointed out when interviewed by Lokteff, noting that “older” conservatism “is like liberalism: they don’t conserve anything, they are just for free markets” (2018b). Women from these circles voting for Trump was merely strategic: as Lokteff remarks, “Let’s be honest, he’s not one of our guys. We’ve never thought that he’s one of our guys” (Bowman and Stewart 2017). As Bowman and Stewart conclude, “The thing they are most interested in is promoting the white race and they see him as an opportunity – someone whose coattails they can ride” (2017).

3.2. Race

Racial identity is the second component to consider when locating frustration among tradwomen. Harris-Perry concludes that the findings of an elle.com survey “suggest women’s anger is connected to the political world, not to some innate characteristic of their racial identity” (2018). While, strictly speaking, there is some truth to this statement, the socio-cultural construction of race has maintained uneven relations of power that remain a concern for many and can be translated into anger through various channels, such as politics. DiAngelo finds that in the early 2000s, many experienced what he captures with the expression “white fragility,” which refers to “a state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves” (2011, 54). The prevailing sense of the US becoming multicultural lends authenticity to their general sense of losing white privilege. This permeates the writings of tradwomen, supported further by known figures, such as Southern and her documentary Farmlands (2018), which she shot investigating white genocide in South Africa. In a 2018 video recording, Lokteff brought the trope of genocide home when attacking the media for the unproblematized representation of interracial couples, noting that “this dirty propaganda is trying to destroy, in whole or in part, a group of people and trying to prevent births within that group. That, folks, constitutes as genocide” (2018a).

Right-wing influencers often draw on demographics to illustrate their points (Holt 2017). “Seventeen states had more white deaths than births in 2014, compared to just four states in 2004,” conclude Saenz and Johnson (2016, 1), which contributed to a renewed sense of panic about white privilege and racial or “tribal” preservation, as they call it. The result is twofold: on the one hand, they resent liberal civic nationalism and the multiculturalism it supports because it “ensures their political power,” as Rose, a YouTube influencer argued (quoted in Holt 2017). This view is spurred on by the feeling that the country is under attack by undocumented aliens (Figure 2), culminating in a general fear for the white race and giving way to a heightened sense of xenophobia and Islamophobia. On the other hand, frustration and discontent with the president are also on the raise as Trump does not seem to be sufficiently strong to protect white power, as indicated by his handling of some urgent issues, including his failure to stop Afro-Americans’ constant push for “equal” recognition, e.g. #BlackLivesMatter; his inability to put a complete halt to undocumented immigration; and his failed effort to protect the southern borders with the construction of a border wall, which was supposedly so effective in defending some of Europe from migrants (see Southern 2019). After all, good fences make good neighbors.

Many are also concerned about the #BlackLivesMatter movement, which seems to have evolved into a volcano that may erupt at any moment, causing further destruction and loss of lives. Bowman and Stewart (2017) refer to Lokteff, who claims that this movement silences and thus oppresses white people. In her interview with Ayla Stewart, Gordon (2018) finds that among the various concerns that raise her temper, she views Black and Muslim crime in particular with apprehension, along with Silicon Valley (meaning online) “enabling” pedophilia and racial integration in schools. The separation of races is a cardinal principle of white supremacists in particular, who insist on eugenics, the maintenance of separate racial blood lines. Lokteff, for one, considers it her priority to expose why maintaining racial purity is imperative, setting some European states as good examples for ethnic and cultural purity (2018a, see also Holt 2017).

3.3. Class

Although the primary sources do not contain explicit references to class positions, various comments allow one to draw conclusions about some of “the hidden injuries of class” (Gorman 2017). Trump appealed to masses through his generic campaign slogans “Make America great again!” or “America first!” which represented his promises to improve the American economy by re-negotiating trade deals, raising tariffs and cutting taxes as well as creating new jobs – all of which resonated with the lower half who felt economically dispossessed and deprived. Many feel disappointed by the slow delivery on these promises – and continue to feel left behind. Within the working class in particular, finds Gorman, there is “a tendency for angry white men (and women) to lash out at the wrong social forces” (2017, 11) – such as “middle- and upper middle-class, white-collar workers, minorities, women, and Muslims” (2017, 6). As the result, their status remains untouched, which exacerbates their hopelessness and fury further.

Many women share in what Lokteff put as follows: “Some of the white guys are kind of mad right now when they’re literally on the shit list. They’re last in line for schools, for loans, for jobs, for grants” (quoted in Holt 2017). Appropriating the logic of victimization and aggrieved entitlement allows tradwomen to identify with the grievances of their “injured” male family members, particularly husband or son, and respond emotionally to the loss of what they construct as a mythic past of abundance and harmony, which they praise with a sense of nostalgia. Kelly (2018) shares similar sentiments from the perspective of young white women she has interviewed:

"We shouldn’t underestimate how some young white women, when faced with this bleak economic landscape and then presented with a rosy image of 1950s domestic bliss, may look back to 1960s Friedan-era feminism as having cheated them out of a family and a luxurious lifestyle, all supported by a single income. The men on the alt-right might point to diversity initiatives and mass immigration as having dismantled their career prospects; the women are furious that they have to consider career prospects at all."

A booming economy that ensures job security, higher income levels and respectable financial status used to comprise some of the building blocks of white male privilege, which, they believe, was washed away by liberal support for multiculturalism and feminism. They see economic hardships as a consequence of immigrants taking jobs from white men and white women being forced to compete on the job market with their men – as Critical Condition argues in an interview with Lokteff (2018b).

Many women, as Lokteff duly notes, are also concerned about postsecondary education having become a business undertaking, with extremely high tuition fees that often exclude children from lower-income families. Grants are typically set up to favor particular minority groups, so talent and a modest family income is typically no longer sufficient to meet application requirements. The economic burden that accompanies higher education was denounced by Sarah Palin’s famous anti-establishment claim: “My kid is not your ATM!” In addition, they often associate elite education with the inner circles of Washington, DC, and with a rather liberal world view and value system that they believe characterize American postsecondary education. No wonder that in another program Lokteff agrees with Critical Condition in that liberalism is “like a cult” (see also Stewart 2019) and that universities are their “brainwashing institutions” (2018b), a way of thinking that also gibes with the tendency of anti-intellectualism – although Gorman finds that half of the working class parents he interviewed consider higher education desirable for their children (2017, 117). Since they have great pride in being hard-working white people, even if working class, their inability to support their children financially to get a degree fills many of them with resentment of the system. In addition, Critical Condition reflects on higher education in relation to gender and expresses her annoyance over women attending universities “wasting their best childrearing years” (Lokteff 2018b) and suggests that they should start a family and can educate themselves later in life.

The ever-recurring debate over gun control continues to be high on the list of topics that energizes some tradwomen and their families (Gordon 2018). Even though they condemn school shootings and the potential loss of innocent lives, they perceive the Second Amendment as granting them the right to protect themselves, their family members and possessions and any attempt to revoke it is an elemental threat to them as well as to the Constitution and the nation it undergirds. As part of the Bill of Rights, the Second Amendment symbolically represents the power of the citizens in the face of the government, thus echoing the general Republican anti-establishment rhetoric as well. Another sensitive point regarding government control and regulations in relation to individual responsibility and property is the existence of the Affordable Care Act (Figure 2). Although the original law has been amended under Trump, the feeling that hard-working American citizens must contribute to medical payments for others reaches beyond the limits of solidarity of which they approve. They are deeply troubled by their perception of the federal government forcing them to bear more financial burdens because of a law they never supported, since they believe in individual responsibility for all.

3.4. Religion

Most tradwomen I have encountered are devout Christians – although Lokteff, for one, “identifies as pagan” (Darby 2017), even though she regularly refers to the Bible as an authoritative source. She also claims that the far right includes all kinds of people, from fervent Christians to atheists, although most conservatives tend to be religious. Their belief determines their way of thinking and opinions s well as shape their actions and relations. Tradwomen seem to share a belief in the natural, i.e. biologically determined, order of things, which should be respected and widely shared by all in the US. They maintain, for example, that “God created different nations and languages” (Lokteff 2018b), and did so with a reason, based on which they push for the recognition of homogeneous ethno-nations as the norm in the world. Lokteff, as well as Brittany Sellner (born Pettibone), an American author and vlogger on the right, are each married to well-known European Identitarian public figures and set their movement in Europe and the ethnic-based nation-states it protects as an example for Americans to follow. In addition, they also recognize gender roles in a similarly essentialist vein, arguing that men and women were created to complement each other and that therefore their corporeality determines their social roles and life cycles. Any challenge to this cosmology renders tradwomen disappointed and anxious.

The common understanding that the US is undergoing a powerful secularization – and thus the number of Christians is shrinking (Pew Research Center 2019) – leaves them heartbroken and worried. Perceived as changing legislative measures that serve liberal values, many tradwomen resent the legalization of abortion – in fact, even Republican men are slightly more supportive of abortion rights than women (see Figure 2.). Similarly, they also refuse practices challenging or subverting understandings of heteronormativity and traditional Christian gender positions, such as same-sex marriage and sex or gender reassignment surgery, along with putative intrusions into the balance of nature as designed by the Creator, such as cloning or gene modification procedures. Stewart (2019) summed up their priorities with the following keywords: “Faith, family, freedom. God, guns, guts. Borders, Bibles, babies.” Her Instagram site also provides images that confirm the power of faith, from watercolors depicting rural churches through an image of Jesus on the cross before a dark gray stone wall, reminiscent of his great sacrificial death, to an image of a child’s hands with interlocked fingers while praying, united by a rosary with the cross in the middle of the composition, shining through at us.

Another point of discontent is with public education as a whole: fear for their children’s physical well-being – because of bullying, drug use, school shootings and a desegregated student body – and spiritual development – with the exclusion of religion from the public school system and of “academic fields,” such as creation science or intelligent design. For some of them, private schools affiliated with religious communities provide an outlet (in 2016, 3.8 million students in Grades K–12 attended such schools, see Broughman, Rettig and Peterson 2017, 7), while others may choose home schooling (with 2.5 million students in Grades K–12 receiving this form of education in 2019 out of a total of 56.6 million students, see Ray 2020).

3.5. Gender

Tradwomen conceptualize gender roles within traditional, Christian interpretative frameworks, reminiscent of the nineteenth-century concept of true womanhood, with cherished Victorian virtues, such as piety, purity, submissiveness and domesticity (Welter 1966). They continue to perceive women’s position within the bonds of the nuclear family, and thus they resent contemporary alternative family structures and people who see the need for social transformation. Lokteff (2018b) urges young women: “It’s OK to find a guy to take care of you!” and focus on family, not studying or finding a job, let alone building a career.

Tradwives and tradmoms (Kelly 2018) focus on the family and the home (Lokteff 2018b), which, if “repeated as a sacred chant, has a massive sentimental content … transcending into the visible world from the invisible domain of feelings” (Cristian 2015). Stewart, in particular, encourages home making, with her online content capturing the imagination in restoring traditional lifestyle and family values in a series of compositions of the welcoming, warm and loving atmosphere which her activities as a tradwife and tradmom create on their estate. She also earned fame for issuing what became known as the “white baby challenge” (Gordon 2018, Kelly 2018, No Time for Silence), which not only situates women as mothers first and foremost, but also assigns them the responsibility of saving the white race: they “provide the wombs upon which the collective future of the white race depends” (Gordon 2018). No wonder they lash out at others with a different view because of their fear for their – white – race and culture.

The notion of gender complementarity defines the way they imagine the social role of men and women; consequently, they regard two people of different genders as the basic, natural unit, held together by love, upon which the nuclear family is constructed. The results are twofold: one, women who are single are at times bullied for not being married – which was the case with Southern (2017), who reported she felt the need to explain why she was still single at the age of 22; and, two, as a result of complementarity, tradwomen feel that whatever happens to their men, happens to them as well: they feel their fury for whatever reason, “psychological trauma, political disenfranchisement, downward economic mobility, gradual irrelevance in a globalizing world” (Kimmel 2018, 4). Many white women supported Trump because of the perceived sense of white masculinity hurting and of the “threat that white patriarchy had lost its grip” (Traister 2018, 25). Each time their men are angry, these women are also angry. Belew refers to something similar when noting that within the Ku Klux Klan, women’s and men’s actions “cannot be separated” (quoted in Gordon 2018).

This conceptual framework carries further implications with regard to women who fight for a different gender model, typically referred to as “the feminists.” Many tradwomen’s perspective on feminists tends to be that, by having advocated gender equality, “they corrupted what women are about” (Bowman 2017), which is beauty, family and home, as Lokteff (2017) puts it: “Most women want to be beautiful, attract a guy, be taken care of, have their home, have their children” (quoted in Darby 2017). Some of the more vocal women in the digital world, such as Stewart and Bre Faucheux, lend authenticity to their critical assessment of feminism and liberalism through their own life narratives: they witness to having been college students mesmerized by the left, embracing the fight for racial and gender equality, but then realizing that they had been cruelly misled. Stewart goes as far as to claim that when she was younger, it was actually liberals and feminists who made her sexist and racist through their logic, which implied that “the white man was the enemy – the guy who always had power and control, whom we had to get rid of and get women and people of color into power” (quoted in Darby 2017).

Portraying feminists as their Other who, along with liberals, have historically contributed to the destruction of the ideal traditional lifestyle they long for is rounded out by some specific claims, as seen in a collection of videos available at No Time for Silence. Bianco (2016) notes that some traditional women despise feminists for failing to represent all women and consider it their “ethical failure” that, for example, “black women created their own womanism.” Kelly (2018) reports that among them, “fears of objectification and sexual violence remain as potent as ever; the tradwife subculture exploits them by blaming modernity for such phenomena, and then offers chastity, marriage and motherhood as an escape.” She also recalls a young YouTuber arguing that “traditionalism does ‘what feminism is supposed to do’ in preventing women from being made into ‘sexual objects’ and treated ‘like a whore’” (Kelly 2018). This is their discoursal version of traditional white female injury suffered from feminist misconduct and failure, and the fact that they have to bear the consequences both hurts and angers them deeply.

4. Conclusion

Tradwomen comprise a heterogeneous group, and, although some things unite them, other things divide them. As a result, the issues that concern them cover a wide spectrum, some of which have been discussed in this paper, in connection with politics, race, class, religion and gender. The issues that find an outlet through their anger delineate cracks within the American social landscape, some so prevalent that they divide it like deep canyons. Still, it is one landscape.

In the broader context, there are two important perceptual considerations with regard to women and American society. One, tradwomen whose life narratives and views have been explored in this study conceptualize themselves within the context of their marriage and family, their womanhood gains the core of its meaning in this arrangement. This means, therefore, that they draw the primary boundary of their identity as a woman around the family unit, and not themselves. Thus, whatever happens to their husband or son, happens to them as well. As a result, they define themselves in relation to society through the traditional nuclear family model, and hence traditional masculinity and patriarchy. In their study of white women’s voting preference during the 2016 election, Strolovitch and Wong (2017) conclude that women inclined to vote GOP had a “possessive investment” both in whiteness and heteropatriarchy, which this study also confirms. And the primary site where they can grasp and act upon these investments remains the family. A number of women, even in alt-right or extremist groups, have noted that they are aware of issues regarding the misogynistic and abusive ways some men tend to treat women, which may be one specific area that may undermine this unity. However, they believe that it seems negligible in relation to – if not as a result of – the changes around them: the putative disenfranchisement and emasculation that the American political establishment, liberals, feminists, various minority groups have forced on white men; thus, these white men are excused and acquitted. These women will not turn against their husbands and children to demolish patriarchy in the name of some vague sisterhood either, and pursuits conceived as attacks on hegemonic masculinity are perceived as attacks on these women themselves. Therefore, they will align with their husbands even more in the face of those.

Two, the pattern thus confirms that there is no united sisterhood in the US, so any presumption that women share in the same broad goals and have a similar set of ideals as for what a democratic society should deliver to them is false. “Women’s suffrage was the catalyst that brought women across the political spectrum together, but once their initial goal was achieved, any sense of unity went out the window,” as one of Gordon’s interviewees noted (2018; see also Schreiber 2008, 19). Lokteff even claims that feminism “did not make things better for women … But it did make them worse for men” (quoted in Darby 2017). Therefore, the general perception that the long fight for gender equality is seen by all as having granted more freedom and power to all women is not quite right. Nor is it accurate that that it left traditional womanhood and femininity untouched and had no wash-back effect on what had been the reality for them. Somehow the question of how subsequent changes affected traditional women seems to have been ignored: they were possibly left behind without much thought or based on the conviction that they can continue to lead their lives as they please. But many of them could not. When lost, privilege, which is always conceived as deserved, can always hurt and anger some, and they would require attention to understand how their perceived sacrifices have contributed to a better, more egalitarian society and how those perceived sacrifices could benefit them.

Back in 1853, Sojourner Truth asked “Ain’t I a woman?” in a powerful speech that pointed to intersectionality in a sharp, direct manner. In a similar vein, we may ask today, “Aren’t tradwives your sisters?” Since its inception, intersectionality has evolved into an analytical framework to address uneven power relations and reveal systematic structural oppression, but then, it can also be utilized as a tool to map the whole social landscape to determine specific beliefs, social positions, life chances and concerns, etc. An investigation of this nature may shed light not only on differences between various social formations defined through intersectionality, but also on similarities in terms of fears, drives and desires, which may be beneficial in the long run to attempt to move towards collaboration of some kind, as angry white women should not be ignored if we are devoted to investing in the creation of a more egalitarian society. Those canyons need to be bridged.

Works Cited

- Annus, Irén. 2015. “Pants Up in the Air: Breaking Bad and American Hegemonic Masculinity Reconsidered.” Americana e-Journal of American Studies in Hungary, 11:1. Web: http://americanaejournal.hu/vol11no1/annus

- Bianco, Marcie. 2016. “What sisterhood?” Quartz, November 14, 2016. Web: https://qz.com/835567/election-2016-white-women-voted-for-donald-trump-in-2016-because-they-still-believe-white-men-are-their-saviors/

- Blee, Kathleen M. 2002. Inside Organized Racism: Women in the Hate Movement. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Blee, Kathleen M. 2009. Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bowman, Emma and Ian Stewart. 2017. “The Women Behind the ‘Alt-Right.’” NPR, August 20, 2017. Web: https://www.npr.org/2017/08/20/544134546/the-women-behind-the-alt-right?t=1588161398724

- Bowman, Karlyn. 2018. “How Angry Are We? What the Polls Show.” Forbes, December 17, 2018. Web: https://www.forbes.com/sites/bowmanmarsico/2018/12/17/how-angry-are-we-what-the-polls-show/#1cc265762a65

- Broomfield, Matt. 2017. “Women’s March against Donald Trump is the Largest Day of Protest in US History, Say Political Scientists.” The Independent, January 23, 2017. Web: https://web.archive.org/web/20170125182025/http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/womens-march-anti-donald-trump-womens-rights-largest-protest-demonstration-us-history-political-a7541081.html

- Broughman, Stephen, Adam Rettig and Jennifer Peterson. 2017. Characteristics of Private Schools in the United States: Results from the 2015-2016 Private School Universe Survey First Look. Washington, DC: National Center for Educational Statistics. Web: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2017/2017073.pdf

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 1998. “It’s All in the Family: Intersections of Gender, Race, and Nation.” Hypatia, 13:3, 62-82.

- CNN. 2016. Election 2016: Exit Polls. Web: https://edition.cnn.com/election/2016/results/exit-polls

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review, 43:6, 1241-99. Web: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1229039

- Cristian, Réka M. 2015. “Home(s) on Borderlands and Inter-American Identity in Sandra Cisnero’s Works.” Americana e-Journal of American Studies in Hungary. 11: 1. Web: http://americanaejournal.hu/vol11no1/cristian

- Darby, Seyward. 2017. “The Rise of the Valkyries.” Harper’s, September 2017. Web: https://harpers.org/archive/2017/09/the-rise-of-the-valkyries/

- DiAngelo, Robin. 2011. “White Fragility.” International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3:3, 54-70. Web: https://libjournal.uncg.edu/ijcp/article/viewFile/249/116

- Draut, Tamara. 2018. “Understanding the Working Class.” New York: Demos. Web: https://www.demos.org/sites/default/files/publications/WorkingClass_Explainer_Final.pdf

- Ebner, Julia and Jacob Davey. 2019. “How Women Advance the Internalization of the Far-Right.” In: Alexander, Audrey (ed). Perspectives on the Future of Women, Gender, and Violent Extremism. Washington, DC: George Washington University, 32-39. Web: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/bc4b/79570b130697e23508df222de24fd03beaae.pdf

- Evans, Sophie J. 2019. “Spreading Hate: The far-right ‘Barbies’ luring Brit girls with promise of luxury lifestyle, ‘star’ status and thousands of male admirers.” The Sun, October 9, 2019. Web: https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/10041621/extreme-far-right-barbies-women/

- Frasure-Yokley, Lorrie. 2018. “Choosing the Velvet Glove: Women Voters, Ambivalent Sexism, and Vote Choice in 2016.” Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics, 3, 3-25. Web: https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/2B3663F7A9379ACA058B3F00B0B684DD/S2056608517000356a.pdf/choosing_the_velvet_glove_women_voters_ambivalent_sexism_and_vote_choice_in_2016.pdf

- Freeman, Joanna. 2018. “America Descends into the Politics of Rage.” The Atlantic, October 22, 2018. Web: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2018/10/trump-and-politics-anger/573556/

- Gordon, Glenna. 2018. “American Women of the Far Right.” The New York Review of Books, Dec 13, 2018. Web: https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2018/12/13/american-women-of-the-far-right/

- Gorman, Thomas J. 2017. Growing Up Working Class: Hidden Injuries and the Development of Angry White Men and Women. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Griffin, Rachel Alicia. 2012. “I AM an Angry Black Woman: Black Feminist Autoethnography, Voice, and Resistance.” Women’s Studies Communication, 35:2, 138-157. Web: DOI: 10.1080/07491409.2012.724524

- Harris-Perry, Melissa. 2018. “Fired up.” Elle, March 9, 2018. Web: https://www.elle.com/culture/career-politics/a19297903/elle-survey-womens-anger-melissa-harris-perr

- Hawley, George. 2017. Making Sense of the Alt-Right. New York: Columbia.

- Holt, Jared. 2017. “Alt-Right You Tube Stars Stop Pretending, Give Full-Throated Endorsement of Ethno-Nationalism.” Right Wing Watch, December 8, 2017. Web: https://www.rightwingwatch.org/post/alt-right-youtube-stars-stop-pretending-give-full-throated-endorsements-of-ethno-nationalism/

- hooks, bell. 1992. “The Oppositional Gaze.” In Black Looks: Race and Representation. Boston: South End, 112-132.

- Junn, Jane. 2016. “Hiding in Plain Sight: White Women Vote Republican.” Politics of Color, November 13, 2016. Web: http://politicsofcolor.com/white-women-vote-republican/#disqus_thread

- Kelly, Annie. 2018. “The Housewives of White Supremacy.” The New York Times, June 1, 2018. Web: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/01/opinion/sunday/tradwives-women-alt-right.html

- Kimmel, Michael. 2017. Angry White Men: American Masculinity at the End of an Era. New York: Nation Books.

- Kimmel, Michael. 2018. Healing from Hate: How Young Men Get Into – and Out of – Violent Extremism. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Kimmel, Michael. 2012 [1998]. Manhood in America: A Cultural History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kovács, Ágnes Zsófia. 2018. “To Harness Discontent: Michelle Obama’s Becoming as African American Autobiography.” Americana e-Journal of American Studies in Hungary, 14: 2, Web: http://americanaejournal.hu/vol14no2/kovacs

- Lokteff, Lana. 2017. “How the Left Is Betraying Women.” Red Ice TV, March 9, 2017. Web: www.youtube.com/watch?v=n2TttaubPCY&t=85s

- Lokteff, Lana. 2018a. “Interracial Relationships More Devious that Mass Murder.” Red Ice TV, June 11, 2018. Web: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ds_2s0xEyQY&feature=emb_title

- Lokteff, Lana. 2018b. “Too Many Women at University: Interview with Critical Condition, Vlogger.” Red Ice TV, May 8, 2018. Web: https://redice.tv/red-ice-tv/too-many-women-at-university

- McRae, Elizabeth. 2018. Mothers of Massive Resistance: White Women and the Politics of White Supremacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- “No Time for Silence.” n.d. Web: https://notimeforsilence.wordpress.com/white-women/

- Pew Research Center. 2019. “In U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace.” Pew Forum, October 17, 2019. Web: https://www.pewforum.org/2019/10/17/in-u-s-decline-of-christianity-continues-at-rapid-pace/

- Ray, Brian D. 2020. “Research Facts on Homeschooling: Homeschool Fast Facts.” Salem, OR: National Home Education Research Institute. Web: https://www.nheri.org/research-facts-on-homeschooling/

- Saenz, Rogelio and Kenneth M. Johnson. 2016. “White Deaths Exceed Births in One-Third of U.S. States.” Casey Research 110, Fall 2016, 1-8. Web: https://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1288&context=carsey

- Schreiber, Ronnee. 2008. Righting Feminism: Conservative Women and American Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Southern, Lauren. 2019. Borderless. Film. Web: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y3ymVkLYV3Y

- Southern, Lauren. 2018. Farmlands. Film. Web: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a_bDc7FfItk

- Southern, Lauren. 2017. “Why I am not Married.” Web: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P-UKPpmQlys

- Standing, Guy. 2011. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. London: Bloomsbury.

- Stewart, Ayla. 2019. “Wife with a Purpose.” Web: https://wifewithapurpose.com/About-us/

- Still, Ashlyn, Chris Kahn and Grant Smith. 2018. “American Anger.” Reuters.com, October 24, 2018. Web: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-election-poll-anger/americans-anger-may-help-democrats-in-nov-6-vote-reuters-ipsos-poll-idUSKCN1MY18T

- Strolovitch, Dara and Janelle Wong. 2017. “Centering Race and Gender, Intersectionality.” Political Science Now, January 7, 2017. Web: http://politicalsciencenow.com/2016-election-reflection-series-centering-race-and-gender-intersectionally/

- Traister, Rebecca. 2018. Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Welter, Barbara. 1966. “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860.” American Quarterly 18:2:1, Summer 1966, 151-174. Web: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2711179

- Wiegman, Robyn. 1999. “Whiteness Studies and the Paradox of Particularity.” Boundary 26:3, 115-150. Web: http://www.jstor.org/stable/303743

- Yarrow, Andrew. 2018. Man Out: Men on the Sidelines of America. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institute.

Appendix

Figure 1. 2016 Presidential Election, Demographic Vote Share (CNN, 2016) ↩

Figure 2. Emotional response to key domestic issues, 2018 (Still, Kahn and Smith 2018) ↩

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.