Cultural Institutions, State-sanctioned Narratives and Identity in Mexicali1

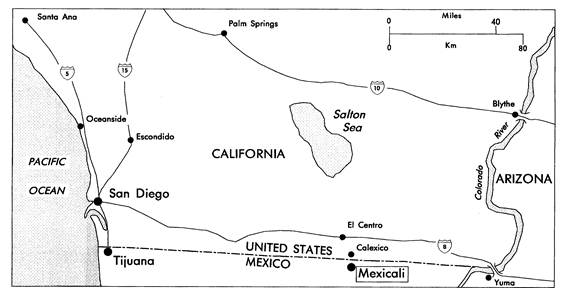

The desert city of Mexicali, the current capital of Lower California state, was founded circa 1904. From the beginning, it was a town largely populated by Chinese rural workers who immigrated to the valley of Mexicali to work in the cotton fields. Their presence has been hailed as key in the founding of the city, according to popular tradition. Mexicali is located on the border with the state of California, across from the city of Calexico (the names of both cities, it is often repeated, were formed with the names of California and Mexico: Cal-exico and Mexi-cali). The city of Mexicali is part of a larger and functionally integrated border region. Its maquiladoras or sweatshops provide thousands of jobs to Mexicans, and are central in the local economy and in manufacturing spare parts of machinery and other goods that carry American brand names.

Figure 1. “Regional Setting of Mexicali.”2

In 2006 the Centro de Investigaciones Culturales-Museo (Center for Cultural Research-Museum, or CCR-Museum), a Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (UABC) center dedicated to the promotion of culture and history, opened its doors in Mexicali. From its inception, the CCR-Museum was joined to a former municipal museum, and since then both institutions have been part of the Mexicali campus of the UABC. Four years ago, as part of a larger three-week program called “Viajeros somos y al museo vamos” (“We are explorers and to the museum we travel”3), I taught a one-week workshop to show young children how historians work.

The three-week workshop is aimed at primary school children ages 7-12. Other sections of the course focus on what ethnographers and archaeologists do. The courses are taught primarily by CCR-Museum staff. Between 20 to 25 children enroll each summer session. We use play and storytelling to interest children in these disciplines of the social sciences and the humanities.

The workshop therefore supplements the formal school curriculum and helps children navigate the confusing web of history and identity in a border-town like Mexicali, which presents special challenges because of its proximity to the United States, and its foundation by Chinese immigrants. Teaching history in an institution like ours in a site such as Mexicali provides a unique opportunity to understand how national “official” history is viewed from the periphery, how identity is constructed in contrast with the “other,” and who this “other” is: US citizens across the border or Mexicali Chinese?

Lower California has its own particular history. For many years it was a “territory” of Mexico, becoming a state of the Mexican federation only in January 1952. Well into the 20th century, the American government and even private American citizens made repeated attempts to purchase or take over the entire peninsula. Some “visionary” Americans sought to attach Lower California to the United States either peacefully or by force.4

Given this background, it seemed to me it would be reasonable to expect a strong current of nationalism in Baja’s primary schools, a tendency that would be reflected in the teaching (and learning) of history. My major interest while approaching my students was therefore to answer the following questions: Is Mexican history taught any differently in Baja California from how it is taught in “mainland” Mexico or does it follow the lines imposed by the Mexican government through its textbook program? Are there any indications of nationalism or xenophobia in the ways Mexicali children imagine life on the other side of the border? Are they aware of the continuous existence of a major Chinese population in the city?

With these questions in mind, over the course of five days I used several techniques to gauge the extent to which primary school students have learned and interpreted Mexican history.5 As a newcomer to the area I was also interested in ascertaining the ways in which Baja California’s past is linked not only to mainland Mexico, but also to California’s (i.e. American) history. A good source to find out about how history is taught, I thought, was through the third grade textbook Baja California: historia y geografía,6 part of the larger Mexican Free Text Program (or Libros de texto gratuitos), which has a long history.

The Mexican Free Text Program became controversial from the start in the 1960s for “its universal, compulsory character…. Further, the texts would be mandatory: every school—federal, provincial or private—was required to use them.”7 Three generations of the program have existed since it first was implemented under Adolfo López Mateos (in the 1960s), under Luis Echeverría (in the 1970s) and, more recently, during the presidency of Carlos Salinas de Gortari (in the early 1990s). With the exception of the last (and more controversial) version of the program implemented under Salinas, history textbooks had adopted a rather Manichaean or dichotomous view of Mexico’s past. The new version, which later evolved into history texts for third year students, was closer to an “objective” version of Mexican history. However, at the third grade level many of the historical heroes with their trite stories remained, for students to emulate and memorize.8

Animating Histories: Official and Untold Stories

One of the aims of my five-day course was to teach young students how professional historians work and to show them the differences between the official and unofficial history of Mexico. I prepared several examples of the uses and abuses of “official history” to demonstrate how it is written and what this means.

My approach was one of “applied history:” I stressed the role of unconventional history in our understanding of the past. I described the existence of many histories not normally taught or discussed in the textbooks they receive from the Mexican government during the regular school year.9 I told them that historians usually rely on original documents, such as letters and memoirs, as well as on artifacts and paintings. I therefore exposed them to an array of sources that, in addition to published books, reflect the traces left by our ancestors.

I stressed the existence (and experience) of individuals and groups usually overlooked by official historians and whose stories do not appear in those textbooks. One ethnic group practically “forgotten” in history textbooks is the Chinese.10 I underscored the differences in the reception encountered by those who migrated to neighboring Sonora vis-à-vis those who came to Baja California. In Sonora, the Chinese were mistreated, victimized, and even murdered.11 Finally, in the early 1930s, they were expelled from the state. In Baja California, their experience was less harsh; the Chinese eventually became a very influential part of Baja California society.12

Telling my students stories such as these and reading them a short story about a Chinese man in Mexicali, I was able to stress how official history is written and what its meaning is. Among the questions I posed were the following: Why was the history of the Chinese excluded in the state’s official history? Have we maintained any of the traditions the Chinese brought with them to our country and, more particularly, to Baja California?13 How do they form part of our daily lives? Could they think of them as people other than waiters at Chinese restaurants?

Figure 2. Cover Page Image of the History Free Textbook.

Figure 3. Chinese hat elaborated with a recycled Free Textbook Poster.

During class—and with the aid from two assistants—we helped children craft their own “Chinese” hats (utilizing, ironically enough, recycled cardboard sheets from posters bearing the title page of the history textbooks so much in vogue in the late 1960s and early 1970s): that way they would feel what it was like to be protected from the sun, Chinese-style. These children were thus under the hats—although not inside the shoes—of Chinese men and women.

Figure 4. At the CCR-Museum.

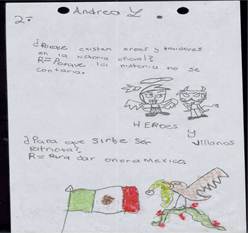

The second day of our workshop I tested some of the ideas I had discussed. I wanted to see what the children had learned. I gave students a set of questions they were to answer at home. In the following drawing I present the both questions and answers of one of my students, 11-year old Andrea L. Morán-Gómez:

Figure 5. Homework by Andrea L. Morán-Gómez.

My first question (“What is the role of ‘heroes’ and ‘traitors’ in Mexico’s official history?”) was aimed at ascertaining if the students had assimilated the fact that Mexican official history was often written in Manichaean or dichotomous terms. Andrea interpreted the question to read as “Why do ‘heroes’ and ‘traitors’ exist in Mexico’s official history?” She answered: “because otherwise history would not be written.” To the question “What is the purpose of being a patriot?” She wrote: “to honor Mexico.”

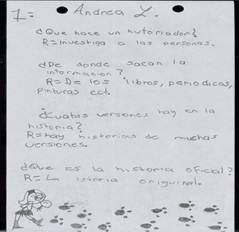

I was surprised to see how much she had learned from my PowerPoint presentations. Her drawings were also meaningful. In answer to question as to “why do ‘heroes’ and ‘traitors’ exist in Mexico’s official history?” she drew an angel and a devil. The religious connotations of these images are significant. The heroes, at least to her, were “angelical,” whereas the traitors (she called them “villains”) were devilish. Interestingly, the angel bears a striking resemblance to the cartoon Timmy Turner, as shown below, and this would suggest some influence of the US media on Mexicali children.

Figure 6. Timy Turner with Evil Foe in Mexicali.

In answer to my question, “What is the purpose of being a patriot?” Andrea—the great grandchild of Melitón Aguilera Pesqueda, a 15-year old youth who “was taken to war” and who “fought side by side with Pancho Villa and Venustiano Carranza,” two leaders of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920)—drew what perhaps is one the most ingrained national symbols in children’s minds: the Mexican flag.

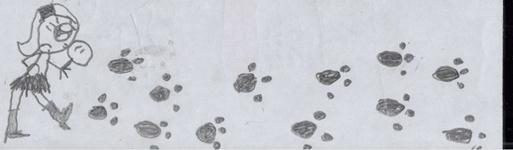

But instead of including the Mexican emblem (the eagle standing on a prickly pear cactus devouring a serpent) as part of the banner, she placed both animals struggling next to it. She drew only a brown stain on the white section of the Mexican flag. (Did she mean to separate the particulars of the struggle, again to show in detail how Mexico’s official history’s eternal fight between absolute opposites was represented at the core of the flag?). While Andrea had drawn her other images in black and white, in this drawing she used green, white and red to show her knowledge of the flag’s colors. Lastly, she drew a girl (with a striking resemblance to girl detective Nancy Drew14) following tracks with a magnifying glass under–although not necessarily in response to–the question “What is ‘official history?’”

It is perhaps significant to note that the tracks she depicted are bears’ footprints rather than the footprints of a more common Mexican animal. In fact, the footprints are similar to those usually found in cartoons. This could be considered another example of how marketing or US television (more than the cold and cardboard-like drawings that appear in most history textbooks, which in Mexico have failed to develop attractive characters) shapes the vision border-town children have of their own world.15

Figure 7. Nancy Drew Follows Historical Traces in Mexicali.

Children’s Representations of Local and Global Identities

In addition to teaching about the historian’s craft, I was interested in reflecting on the importance of the study of history for our present lives. I did this through different approaches and practical activities. During the 2007 summer session I focused more on “intellectual” discussions regarding who was included and who was left out of the official history books. I used comparative history to show how the immigrant experience of a particular ethnic group—e.g., the Chinese—could be radically different from one state to another in Mexico (or, for that matter, anywhere else in the world).

I was interested in gauging the understanding children had of national history and where their state (Baja California) fitted in the larger picture. I also exposed them to the notion of how the sources—or lack of them—can lead different researchers to dissimilar conclusions and how there is (or can be) more than one historical interpretation, regardless of the event or process under scrutiny.

What did this experience tell me about the ways in which Mexicali children feel about the “other”? First of all, the “other” continues to be (officially, at least) the Americans; the Chinese population in Lower California—as depicted in the current state textbook—is close to nonexistent or “invisible.”

There are some preliminary conclusions I would like to underscore, with my very limited field experience. Children don’t seem to harbor any feelings against the United States and have assimilated well-known cartoons and incorporated them into their own (historical or not) narratives. They don’t appear to make any distinctions between themselves and American children, insofar as they have assimilated the same type of “heroes” from US cartoons.

Although officially Chinese are close to “non-existing,” I was nevertheless able to detect some anti-Chinese feelings in at least two of the children in my workshop. As soon as one of them saw my PowerPoint presentations on Chinese migration to California, he began casting slurs on the local Chinese population; the other one began imitating “Chinese talk” and reshaping his eyes to “look Chinese.” This led me to believe that, although not recognized as an important part of Mexicali society, Chinese are seen by some of the children as the “other.” Mexicali children don’t have “almond-shaped” eyes and are not dirty, two of the features these children seemed to associate with the Chinese.

Figure 8. Trying to Look Like the “Other.”

Figure 9. Subtle Ways of Marking the “Difference.”

While globalization would seem to obliterate cultural borders in towns like Mexicali, and this in turn would blur local identities, it seems fairly safe to conclude that children define themselves as non-Chinese but not necessarily as non-American. While they had little to say when they found out that there were some cultural customs in their everyday lives they had inherited from the Chinese, they still found them foreign to their traditions. At the same time, children such as Andrea L. Morán-Gómez have internalized so many American cultural characters that they have incorporated them into their own personal narratives.

It may be that, as one postmodern author expresses it, “contradictory images of the United States in Mexico can co-exist, combining aspects of resistance and assimilation.”16 But such coexistence is not limited to adult Mexicans divided in how they view their nation’s relationship to the United States. The division is manifested in the way children have assimilated American cartoons without even knowing they are an imported and foreign part of their education.

Notes

1 I thank Dr. Annette B. Ramírez de Arellano for her comments and help in better structuring this article, and acknowledge Dr. Thomas Herman’s suggestions to revise and shorten an earlier version. ↩

2 Source for the “Regional Setting of Mexicali” map: James R. Curtis, “Mexicali’s Chinatown,” Geographical Review 85.3 (Jul., 1995): 335-348, at 336. ↩

3 In fact this is a play of words derived from a popular song: “Arrieros somos y en el camino andamos:” “Muleteers we are and on the road we meet.” ↩

4 For an account of several attempts to take over the peninsula, see, for instance, Eugene Keith Chamberlin, “Mexican Colonization versus American Interests in Lower California,” The Pacific Historical Review 20.1 (Feb., 1951): 43-55. Arthur E. North, who traversed the peninsula in 1906, regretted that his government had missed the chance to acquire (through legal or armed means) Lower California. See his Camp and Camino in Lower California (New York: The Premier Press, 1910), particularly his Chapter IV: “Uncle Sam’s Lost Province.” ↩

5 I am basing my findings and assumptions on the experience derived from my interaction with roughly from 20 to 25 students whose parents registered them voluntarily for the CCR-Museum’s three-week 2007 summer program. ↩

6 See Lucila del Carmen León Velazco, Antonio de Jesús Padilla Corona and Marco Antonio Samaniego López, Baja California: historia y geografía, tercer año (Mexico: Secretaría de Educación Pública, 1999). ↩

7 Dennis Gilbert, “Rewriting History: Salinas, Zedillo and the 1992 Textbook Controversy,” Mexican Studies / Estudios Mexicanos 13.2 (summer, 1997): 271-297, at 274. The program included textbooks for the fourth, fifth and sixth grades of primary school. ↩

8 Under Secretary of Education Ernesto Zedillo I participated—together with nine graduate students—in the writing of the Colima history textbook for the third grade. Because of the prize money involved (over US $150,000.00), a problem ensued that lead one of the students to attack me physically at the Universidad de Colima campus. The student, a local politician and personal friend of the president of the university—at the time intent on becoming governor of the state—was allowed to continue his studies while I was removed from my teaching responsibilities and administrative position. The final version of the textbook, which I was not permitted to see (under orders dictated by our future governor), not only underscored the trite actions attributed to Mexican “heroes” and “traitors:” it was filled with historical errors. ↩

9 At one of our first meetings in Colima with the state representative of the Secretaría de Educación Pública, we were asked to remove one of the topics I included in the Colima textbook: the 1920s anti-government uprising of Catholics known as the “Cristiada.” The last version of the book came out with a watered-down version of the rebellion and its causes. ↩

10 In fact and to my own surprise, the third year textbook I quoted above—Baja California: historia y geografía—had only one picture of the Chinese colony and a five word caption: “Desfile de la colonia china:” “Chinese Colony parade.” ↩

11 There is a large and growing literature on the Chinese migratory experience to Sonora. See, for instance Evelyn Hu-DeHart, “Racism and Anti-Chinese Persecution in Sonora, Mexico, 1876-1932,” Amerasia Journal 9 (1982):1-28; Idem., “Immigrants to a Developing Society: The Chinese in Northern Mexico, 1875-1932,” The Journal of Arizona History 21 (1980): 275-312, and Gerardo Rénique, “Race, Region, and Nation: Sonora´s Anti-Chinese Racism and Mexico’s Postrevolutionary Nationalism, 1920s-1930s,” in Race & Nation in Modern Latin America, edited by Nancy P. Appelbaum, Anne S. Macpherson, and Karin Alejandra Rosemblatt (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 211-236. ↩

12 For two articles that delve into the presence of Chinese immigrants in Mexicali’s border society, see Robert H. Duncan, “The Chinese and the Economic Development of Northern Baja California, 1889-1929,” The Hispanic American Historical Review 74.4 (Nov., 1994): 615-647, and James R. Curtis, “Mexicali’s Chinatown.” ↩

13 One of the examples I used to prove that Mexicans had inherited several traits from the Chinese culture, was that of the “pilón:” the practice of Chinese shop owners to give an additional “something” to their customers, such as an extra few grams of rice or a chunk of solid brown sugar (or piloncillo, from where supposedly the word pilón comes) in return for their buying at their shops. Another institution I claimed that survives to this day throughout the city of Mexicali, is that of the “lavadurías,” or laundries. ↩

14 I thank my Mexicali graduate students, particularly Liliana López León and Diana Merchant, for their insights regarding the Timy Turner and Nancy Drew cartoons. ↩

15 This finding would challenge the more common view about how Mexicans in general regard the US. Mexican political cartoonists, in my view, more than reflecting public opinion, try to influence it. This is why while analyzing political cartoons published in the national press one can easily conclude that Mexicans are anti-American. By looking at the production of children in a border town such as Mexicali, one can arrive at different conclusions. For an analysis of Mexican political cartoons see Stephen D. Morris, “Exploring Mexican Images of the United States,” Mexican Studies / Estudios Mexicanos 16.1 (Winter, 2000): 105-139, passim. ↩

16 Stephen D. Morris, “Exploring Mexican Images of the United States,” 112. ↩

Copyright (c) 2010 Servando Ortoll

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.